The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks

A Yale survey finds that people with high levels of scientific literacy are more culturally polarized. The findings are consistent with the notion that climate change has become highly politicized, but divisions are due to worldviews not merely partisanship.

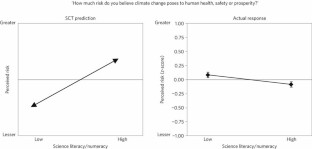

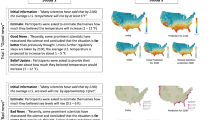

Researchers tested two theories:

1. The "science comprehension thesis": individuals fail to take climate change seriously because they do not understand the scientific evidence (i.e. conflict between scientists and the public.)

- To test the science comprehension thesis, researchers looked at science literacy, numeracy and technical reasoning abilities.

2. The "cultural cognition thesis": individuals form perceptions of societal risk based on the values of peer groups (i.e. conflict between different segments of the public).

- To test the cultural cognition thesis, researchers looked at worldviews, specifically hierarchical/individual v. egalitarian/communitarian worldviews.

WHY YOU SHOULD TAKE A LOOK:

The study suggests that divisions in climate change public opinion are caused not by lack of understanding, but from a conflict between the personal interest people have in forming beliefs that are in line with their peers and a collective interest in promoting common welfare.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

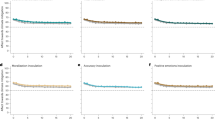

Members of the public with the highest degree of science literacy and technical reasoning capacity were most culturally polarized about climate change.

Controlling for scientific literacy and numeracy, hierarchical individualists were less concerned about climate change than egalitarian communitarians.

- Among egalitarian communitarians, science literacy was positively correlated with climate change concern.

- Among hierarchical individualists, science literacy was negatively correlated with climate change concern.

The reason for this may be "motivated cognition" where individuals express shared worldviews to avoid dissonance with peers:

"For the ordinary individual, the most consequential effect of his beliefs about climate change is likely to be on his relations with his peers. A hierarchical individualist who expresses anxiety about climate change might well be shunned by his co-workers at an oil refinery in Oklahoma City. A similar fate will probably befall the egalitarian communitarian English professor who reveals to colleagues in Boston that she thinks the scientific consensus on climate change is a hoax."

The study found no support for the idea that public apathy over climate change is a result of a deficit in comprehension or technical reasoning. Therefore, as long as the climate debate is imbued with cultural meaning that divides individuals with different worldviews, a communication strategy that focuses only on the science is unlikely to shift public opinion.

Researchers suggest that communicators create an environment where accepting the science doesn't threaten any group's values, such as culturally diverse communicators who share an affinity and credibility with different communities and framing techniques that allow policy solutions to resonate with diverse groups.

Photo via (cc) Flickr user NASA ICE

Related resources

The tragedy of the risk-perception commons: culture conflict, rationality conflict, and climate change, believers, sympathizers and skeptics – climate change and religion, community planning for climate change, nextgen climate/project new america battleground millennial survey, clifibooks: climate change and the arts, global climate change as seen by zoo and aquarium visitors, related resources, welcome to climate access, seven reasons why the public is not engaged on climate, what occupy means for the climate movement, winning the story wars with freaks, cheats and familiars, there's action out there, taking the long view on keystone.

© 2024 Climate Access. All rights reserved. Website by Affinity Bridge

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 May 2012

The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks

- Dan M. Kahan 1 ,

- Ellen Peters 2 ,

- Maggie Wittlin 3 ,

- Paul Slovic 4 ,

- Lisa Larrimore Ouellette 3 ,

- Donald Braman 5 &

- Gregory Mandel 6

Nature Climate Change volume 2 , pages 732–735 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

37k Accesses

1252 Citations

1489 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Climate change

Seeming public apathy over climate change is often attributed to a deficit in comprehension. The public knows too little science, it is claimed, to understand the evidence or avoid being misled 1 . Widespread limits on technical reasoning aggravate the problem by forcing citizens to use unreliable cognitive heuristics to assess risk 2 . We conducted a study to test this account and found no support for it. Members of the public with the highest degrees of science literacy and technical reasoning capacity were not the most concerned about climate change. Rather, they were the ones among whom cultural polarization was greatest. This result suggests that public divisions over climate change stem not from the public’s incomprehension of science but from a distinctive conflict of interest: between the personal interest individuals have in forming beliefs in line with those held by others with whom they share close ties and the collective one they all share in making use of the best available science to promote common welfare.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

A toolkit for understanding and addressing climate scepticism

Changing minds about climate change: a pervasive role for domain-general metacognition

Psychological inoculation strategies to fight climate disinformation across 12 countries

Pidgeon, N. & Fischhoff, B. The role of social and decision sciences in communicating uncertain climate risks. Nature Clim. Change 1 , 35–41 (2011).

Article Google Scholar

Sunstein, C. R. On the divergent American reactions to terrorism and climate change. Columbia L. Rev. 107 , 503–557 (2007).

Google Scholar

Weber, E. U. & Stern, P. C. Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am. Psychol. 66 , 315–328 (2011).

Douglas, M. & Wildavsky, A. B. Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technical and Environmental Dangers (Univ. California Press, 1982).

Kahan, D. M., Braman, D., Slovic, P., Gastil, J. & Cohen, G. Cultural cognition of the risks and benefits of nanotechnology. Nature Nanotech. 4 , 87–91 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H. & Braman, D. Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J. Risk Res. 14 , 147–174 (2011).

Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

Book Google Scholar

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J. & Wagner, G. G. Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 9 , 522–550 (2011).

Ganzach, Y., Ellis, S., Pazy, A. & Ricci-Siag, T. On the perception and operationalization of risk perception. Judgment Decis. Making 3 , 317–324 (2008).

Kahneman, D. Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 93 , 1449–1475 (2003).

Peters, E., Västfjäll, D., Slovic, P., Mertz, C. K., Mazzocco, K. & Dickert, S. Numeracy and decision making. Psychol. Sci. 17 , 407–413 (2006).

Liberali, J. M., Reyna, V. F., Furlan, S., Stein, L. M. & Pardo, S. T. Individual differences in numeracy and cognitive reflection, with implications for biases and fallacies in probability judgment. J. Behav. Decis. Making http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bdm.752 (2011).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob. Environ. Change 21 , 1163–1172 (2011).

Krosnick, J. A., Holbrook, A. L. & Visser, P. S. The impact of the fall 1997 debate about global warming on American public opinion. Public Underst. Sci. 9 , 239–260 (2000).

Sunstein, C. R. Misfearing: A reply. Harv. L. Rev. 119 , 1110–1125 (2006).

Kellstedt, P. M., Zahran, S. & Vedlitz, A. Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Anal. 28 , 113–126 (2008).

Slovic, P. Trust, emotion, sex, politics, and science: Surveying the risk-assessment battlefield. Risk Anal. 19 , 689–701 (1999).

CAS Google Scholar

Cohen, G. L. Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85 , 808–822 (2003).

Downs, A. An Economic Theory of Democracy (Harper, 1957).

Chen, S., Duckworth, K. & Chaiken, S Motivated heuristic and systematic processing. Psychol. Inq. 10 , 44–49 (1999).

Giner-Sorolla, R. & Chaiken, S. Selective use of heuristic and systematic processing under defense motivation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 23 , 84–97 (1997).

Kahan, D. Fixing the communications failure. Nature 463 , 296–297 (2010).

Mercier, H. & Sperber, D. Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 34 , 57–74 (2011).

Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162 , 1243–1248 (1968).

Nisbet, M. C. in Communicating Science: New Agendas in Communication 41–67 (Routledge, 2010).

National Science Board Science and Engineering Indicators, 2010 (National Science Foundation, 2010).

Allum, N., Sturgis, P., Tabourazi, D. & Brunton-Smith, I. Science knowledge and attitudes across cultures: A meta-analysis. Public Underst. Sci. 17 , 35–54 (2008).

Weller, J., Dieckmann, N. F., Tusler, M., Mertz, C. K., Burns, W. & Peters, E. Development and testing of an abbreviated numeracy scale: A rasch analysis approach J. Behav. Decis. Making http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1751 (2012).

Frederick, S. Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Perspectives 19 , 25–42 (2005).

Berry, W. D. & Feldman, S. Multiple Regression in Practice 48 (Sage University Papers Series, Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences no. 07-050, Sage Publications, 1985).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Research for this paper was financially supported by the National Science Foundation, Grant SES 0922714.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Yale University, Yale Law School, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, PO Box 208215, USA

Dan M. Kahan

The Ohio State University, 235 Psychology Building, Columbus, Ohio 43210, 1835 Neil Avenue, USA

Ellen Peters

Cultural Cognition Project Lab, Yale University, Yale Law School, New Haven, Connecticut, PO Box 208215, USA

Maggie Wittlin & Lisa Larrimore Ouellette

Decision Research, 1201 Oak Street, Eugene, Oregon 97401, Suite 200, USA

Paul Slovic

George Washington University, 2000 H Street, N.W, Washington DC 20052, USA

Donald Braman

Temple University, 1719 North Broad St., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122, USA

Gregory Mandel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.M.K., E.P., M.W. and L.L.O. contributed to all aspects of the paper, including study design, statistical analysis and writing and revisions. P.S., D.B. and G.M. contributed to the design of the study, to substantive analysis of the results and to revisions of the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dan M. Kahan .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (pdf 626 kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kahan, D., Peters, E., Wittlin, M. et al. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Clim Change 2 , 732–735 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1547

Download citation

Received : 29 November 2011

Accepted : 24 April 2012

Published : 27 May 2012

Issue Date : October 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1547

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Motivated reasoning about climate change and the influence of numeracy, need for cognition, and the dark factor of personality.

- Fabian Hutmacher

- Regina Reichardt

- Markus Appel

Scientific Reports (2024)

Epistemic Hypocrisy and Standing to Blame

- Adam Piovarchy

Erkenntnis (2024)

Correlations Among High School Students' Beliefs about Conspiracy, Authoritarianism, and Scientific Literacy

- Nikola Synak

- Nikola Šabíková

- Radomír Masaryk

Science & Education (2024)

Scientific reasoning is associated with rejection of unfounded health beliefs and adherence to evidence-based regulations during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Vladimíra Čavojová

- Eva Ballová Mikušková

Current Psychology (2024)

Where is the Motivation in Motivated Numeracy?

- Kathrin Glüer-Pagin

- Levi Spectre

Review of Philosophy and Psychology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

We will call this account the “Science Comprehension Thesis” (SCT). SCT is an extremely popu-lar explanation for conflicts over climate change and various other disputed risks, particularly among commentators who construct secondary interpretive accounts by synthesizing diverse findings from deci-sion science ( Sunstein 2005, 2006, 2007).

We conducted an experiment to probe two alternative answers: the ‘science comprehension thesis (SCT), which identies defects in the publics knowledge and ’ fi ’ reasoning capacities as the source of such controversies; and the identity-‘ protective cognition thesis (ICT), which treats cultural conict as disabling ’ fl the faculties that members ...

One, already adverted to, can be called the “science comprehension. tists think, they predictably fail to take climate change as seriously as scientists believe they should3. The alternative explanation can be referred to as the “cultural cognition thesis” (CCT). CCT po-

scientific evidence? We conducted an experiment to probe two alternative answers: the “Science Comprehension Thesis” (SCT), which identifies defects in the public’s knowledge and reasoning ca-pacities as the source of such controversies; and the “Identity-protective Cognition Thesis” (ICT),

Researchers tested two theories: 1. The "science comprehension thesis": individuals fail to take climate change seriously because they do not understand the scientific evidence (i.e. conflict between scientists and the public.)

One, already adverted to, can be called the science comprehension thesis (SCT). As members of the public do not know what scientists know, or think the way scientists think, they predictably fail to take climate change as seriously as scientists believe they should3.

Sep 8, 2013 · We conducted an experiment to probe two alternative answers: the “Science Comprehension Thesis” (SCT), which identifies defects in the public’s knowledge and reasoning capacities as the source of such controversies; and the “Identity-protective Cognition Thesis” (ICT) which treats cultural conflict as disabling the faculties that ...

May 27, 2012 · Seeming public apathy over climate change is often attributed to a deficit in comprehension. The public knows too little science, it is claimed, to understand the evidence or avoid being misled 1.

science comprehension thesis Attributes public controversy over risks and policy-relevant facts to deficits in the public’s capacity to comprehend scientific evidence.

Synthesizing the evidence, the essay proposes that conflict over what is known by science arises from the very conditions of individual freedom and cultural pluralism that make liberal democratic societies distinctively congenial to science.