The UK education system preserves inequality – new report

- Imran Tahir

Published on 13 September 2022

Our new comprehensive study, shows that education in the UK is not tackling inequality.

- Education and skills

- Poverty, inequality and social mobility

- Social mobility

Link to read article

The Conversation

Your education has a huge effect on your life chances. As well as being likely to lead to better wages, higher levels of education are linked with better health, wealth and even happiness . It should be a way for children from deprived backgrounds to escape poverty.

However, our new comprehensive study , published as part of the Institute for Fiscal Studies Deaton Review of Inequalities , shows that education in the UK is not tackling inequality. Instead, children from poorer backgrounds do worse throughout the education system.

The report assesses existing evidence using a range of different datasets. These include national statistics published by the Department for Education on all English pupils, as well as a detailed longitudinal sample of young people from across the UK. It shows there are pervasive and entrenched inequalities in educational attainment.

Unequal success

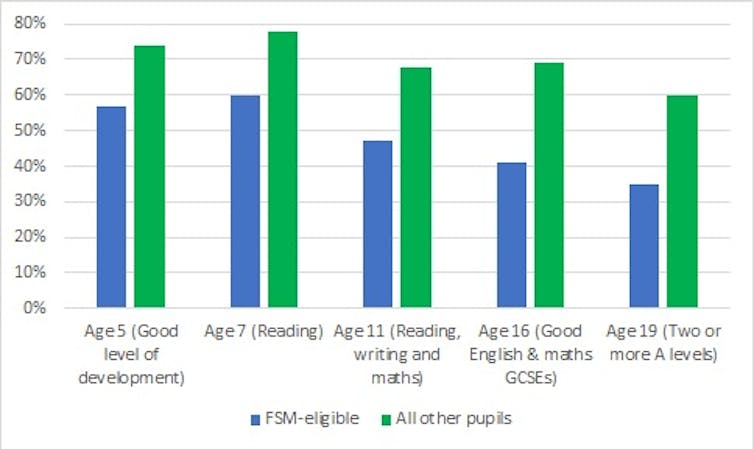

Children from disadvantaged households tend to do worse at school. This may not be a surprising fact, but our study illustrates the magnitude of this disadvantage gap. The graph below shows that children who are eligible for free school meals (which corresponds to roughly the 15% poorest pupils) in England do significantly worse at every stage of school.

Even at the age of five, there are significant differences in achievement at school. Only 57% of children who are eligible for free school meals are assessed as having a good level of development in meeting early learning goals, compared with 74% of children from better off households. These inequalities persist through primary school, into secondary school and beyond.

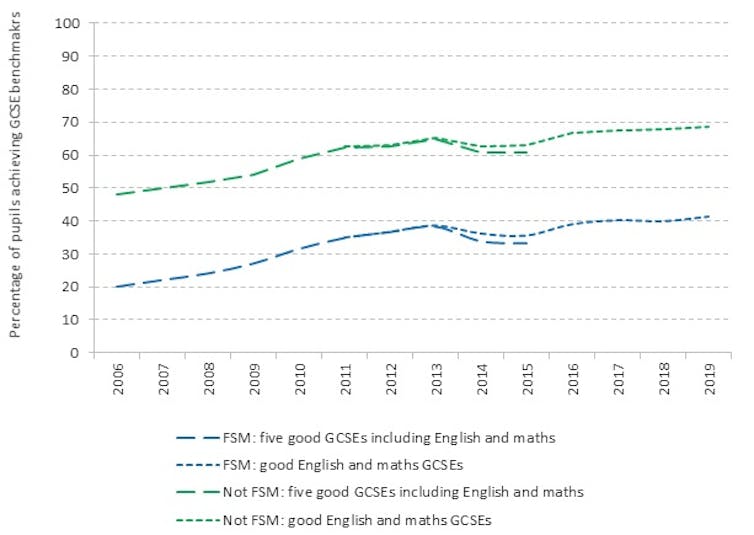

Differences in educational attainment aren’t a new phenomenon . What’s striking, though, is how the size of the disadvantage gap has remained constant over a long period of time. The graph below shows the percentage of students in England reaching key GCSE benchmarks by their eligibility for free school meals from the mid-2000s.

Over the past 15 years, the size of the gap in GCSE attainment between children from rich and poor households has barely changed. Although the total share of pupils achieving these GCSE benchmarks has increased over time, children from better-off families have been 27%-28% more likely to meet these benchmarks throughout the period.

Household income

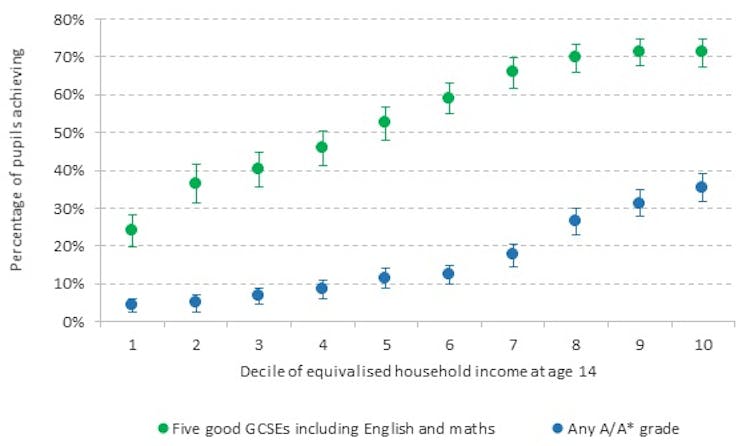

While eligibility for free school meals is one way of analysing socio-economic inequalities, it doesn’t capture the full distribution of household income. Another way is to group young people according to their family income. The graph below shows young people grouped by decile. This means that young people are ordered based on their family’s income at age 14 and placed into ten equal groups.

The graph shows the percentage of young people in the UK obtaining five good GCSEs, and the share obtaining at least one A or A* grade at GCSE, by the decile of their family income. With every increase in their family’s wealth, children are more likely to do better at school.

More than 70% of children from the richest tenth of families earn five good GCSEs, compared with fewer than 30% in the poorest households. While just over 10% of young people in middle-earning families (and fewer than 5% of those in the poorest families) earned at least one A or A* grade at GCSE, over a third of pupils from the richest tenth of families received at least one top grade.

Inequalities into adulthood

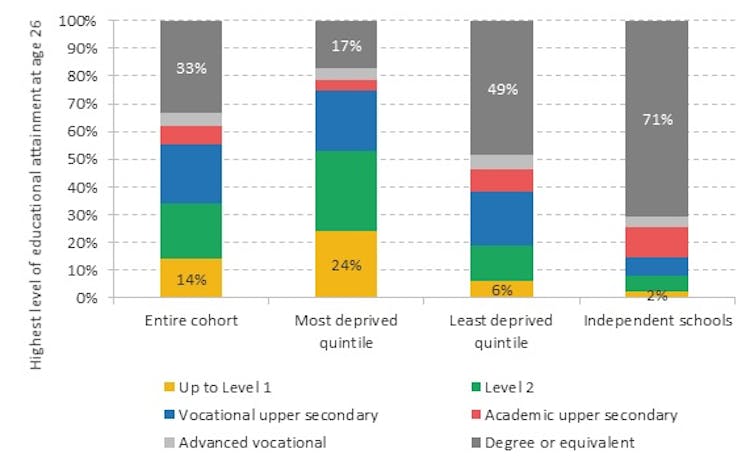

The gaps between poor and rich children during the school years translate into huge differences in their qualifications as adults. This graph shows educational attainment ten years after GCSEs (at the age of 26) for a group of students who took their GCSE exams in 2006.

The four bars show the distribution of qualifications at age 26 separately for the entire group, people who grew up in the poorest fifth of households, those who grew up in the richest fifth of households, and those who attended private schools.

There is a strong relationship between family background and eventual educational attainment. More than half of children who grew up in the most deprived households hold qualifications of up to GCSE level or below. On the other hand, almost half of those from the richest households have graduated from university.

The gap between private school students and the most disadvantaged is even more stark. Over 70% of private school students are university graduates by the age of 26, compared with less than 20% of children from the poorest fifth of households.

Young people from better-off families do better at all levels of the education system. They start out ahead and they end up being more qualified as adults. Instead of being an engine for social mobility, the UK’s education system allows inequalities at home to turn into differences in school achievement. This means that all too often, today’s education inequalities become tomorrow’s income inequalities.

Research Economist

Imran joined the IFS in 2019 and works in the Education and Skills sector.

Comment details

Suggested citation.

Tahir, I. (2022). The UK education system preserves inequality – new report [Comment] The Conversation. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/articles/uk-education-system-preserves-inequality-new-report (accessed: 15 December 2024).

More from IFS

Understand this issue.

How can government reduce child poverty?

We're exploring why there's been an increase in child poverty since 2010 and options the government has to reduce this.

3 October 2024

Buying a home in London in your twenties is difficult, but not impossible

Foregoing a degree for an apprenticeship, saving during Covid and being born and bred in the capital have helped. With sky-high rents, others are not.

25 November 2024

How to reduce child poverty: compare the policy options

Use these charts to compare policies for reducing child poverty and to examine how child poverty rates have changed over time across different groups.

Policy analysis

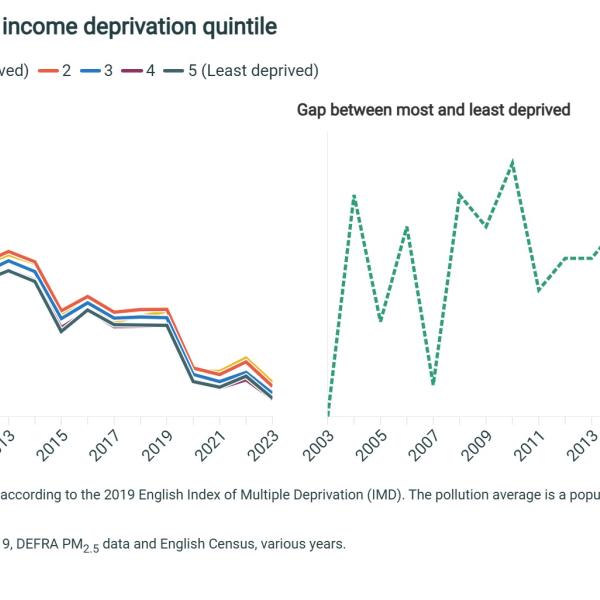

PM2.5 exposure by income deprivation quintile

The most deprived quintile consistently has higher PM2.5 air pollution levels than the least deprived, and this gap has widened since 2017.

6 December 2024

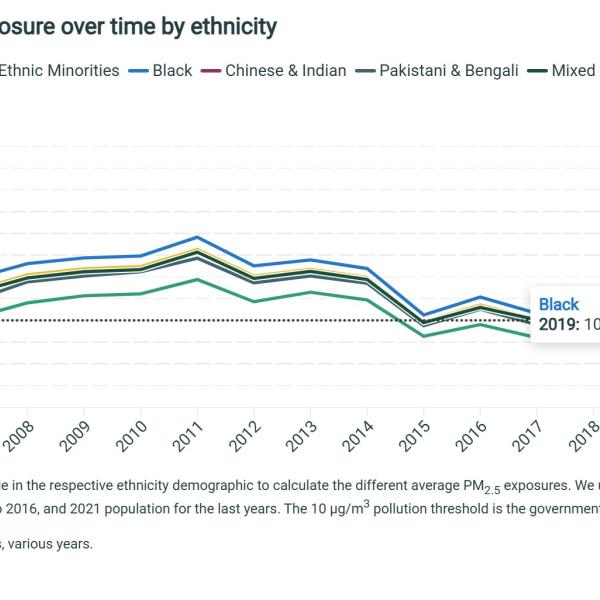

Average PM2.5 exposure over time by ethnicity

Ethnic minorities were exposed to levels of air pollution 13% higher than white populations in 2003; this ‘ethnic pollution gap’ shrank to 6% by 2023.

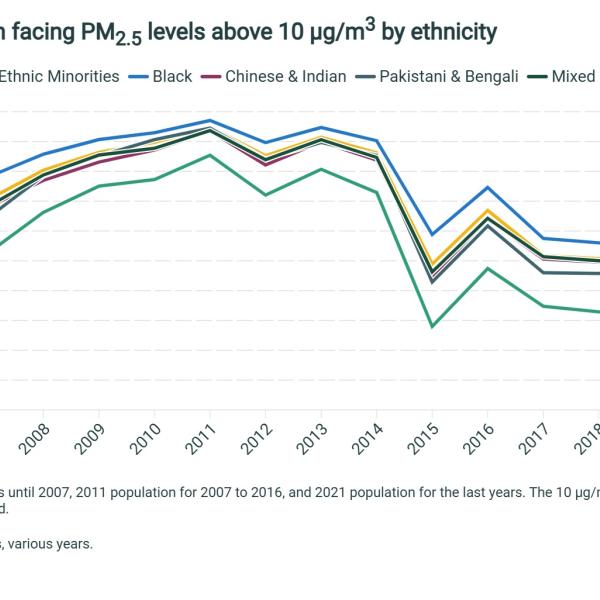

Share of population facing PM2.5 levels above 10µg/m3 by ethnicity

In 2019, 50% of ethnic minorities were exposed to more than 10µg/m3 air pollution. By 2023, this number had fallen to close to zero.

Academic research

The effects of youth clubs on education and crime

Using quasi-experimental variation from austerity-related cuts, I provide the first causal estimates of youth clubs' effects on education and crime.

12 November 2024

Changes in marital sorting: theory and evidence from the US

Measuring how assortative matching differs between two economies is difficult, we show how the use of different measures can create different outcomes

27 November 2024

Schooled by trade? Retraining and import competition

We study the interaction of retraining and international trade in Germany, a highly open economy with extensive state-subsidized retraining programs.

28 October 2024

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Official Statistics on Educational Achievement in the U.K. – Strengths and Limitations

Table of Contents

Last Updated on September 14, 2020 by

How useful are official statistics for understanding differences in educational achievement by social class, gender and ethnicity?

How do GCSE results vary by social class, gender and ethnicity?

The data below is taken from either the Department for Education’s document – Key Stage 4 performance 2019 (Revised), or Gov.uk ‘ ethnicity facts and figures ‘. The later shows data from 2017/18 (at time of writing this), but it is much more accessible than the ‘Key Stage 4 document’.

Firstly – GENDER – Girls outperformed boys in all headline measures in 2019.

For example 46.6% of girls achieved both English and Maths at grade 5 or above, compared to only 40.0% of boys, and girls are much more likley to be entered for the Ebacc than boys (45.9% compared to 34.3%

Secondly – ETHNICITY – Chinese pupils are the highest achieving group . 75.3% of Chinese pupils achieved a ‘strong pass’ (grade 5 or above) in English and Maths, with Indian pupils being the second highest achieving group, at 62%

Black Caribbean pupils have the lowest achievement of any ‘large’ ethnic minority group, with only 26.9% achieving a grade 5 or above in English and Maths

Gypsy/ Roma and Irish Traveller pupils have the lowest levels of achievement with only 9.95 and 5.3% respectively achieving a strong pass in English and Maths.

Thirdly – SOCIAL CLASS – Here, instead of social class we need to use the Department for Education’s ‘disadvantaged pupils’ category, which is the closest we’ve got as a proxy for social class, but isn’t quite the same!

The DFE says that “Pupils are defined as disadvantaged if they are known to have been eligible for free school meals in the past six years , if they are recorded as having been looked after for at least one day or if they are recorded as having been adopted from care”.

In 2019, only 24.7% of disadvantages pupils achieved English and Maths GCSE at grade 5 or above, compared to almost 50% of all other pupils, meaning disadvantaged pupils are only half as likely to get both of these two crucial GCSEs.

Some Strengths of Official Statistics on Educational Achievement by Pupil Characteristic

ONE – Good Validity (as far as it goes) – These data aren’t collected by the schools themselves – so they’re not a complete work of fiction, they are based on external examinations or coursework which is independently verified, so we should be getting a reasonably true representation of actual achievement levels. HOWEVER, we need to be cautious about this.

TWO – Excellent representativeness – We are getting information on practically every pupil in the country, even the ones who fail!

THREE – They allow for easy comparisons by social class, gender and ethnicity. These data allow us to see some pretty interesting trends – As in the table below – the difference between poor Chinese girls and poor white boys stands out a mile… (so you learn straight away that it’s not just poverty that’s responsible for educational underachievement)

FOUR – These are freely available to anyone with an internet connection

FIVE – They allow the government to track educational achievement and develop social policies to target the groups who are the most likely to underachieve – These data show us (once you look at it all together) for example, that the biggest problem of underachievement is with white, FSM boys.

Some Disadvantages of the Department for Education’s Stats on Educational Achievement

ONE – If you look again at the DFE’s Key Stage four statistics, you’ll probably notice that it’s quite bewildering – there are so many different measurements that it obscures the headline data of ‘who achieved those two crucial GCSEs’.

When it comes to the ‘Attainment 8’ or ‘Progress 8’ scores, it is especially unclear what this means to anyone other than a professional teacher – all you get is a number, which means nothing to non professionals.

TWO – changes to the way results are reported mean it’s difficult to make comparisons over time. If you go back to 2015 then the standard was to achieve 5 good GCSEs in any subject, now the government is just focusing on English and Maths, Ebacc entry and attainment 8.

THREE – These stats don’t actually tell us about the relationship between social class background and educational attainment. Rather than recording data using a sociological conception of social class, the government uses the limited definition of Free School Meal eligibility – which is just an indicator of material deprivation rather than social class in its fuller sense. Marxist sociologists would argue that this is ideological – the government simply isn’t interested in measuring the effects of social class on achievement – and if you don’t measure it the problem kind of disappears.

FOUR – and this is almost certainly the biggest limitation – these stats don’t actually tell us anything about ‘WHY THESE VARIATIONS EXIST’ – Of course they allow us to formulate hypotheses – but (at least if we’re being objective’) we don’t get to see why FSM children are twice as likely to do badly in school… we need to do further research to figure this out.

No doubt there are further strengths and limitations, but this is something for you to be going on with at least…

Related Posts

Official Statistics in Sociology

Assessing the Usefulness of Using Secondary Qualitative Data to Research Education

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

2 thoughts on “Official Statistics on Educational Achievement in the U.K. – Strengths and Limitations”

Yess yess lads lads lads and everybody! Yo sociology dudez are epic as! I would like someone to translate this! Yo to you lottt

- Pingback: Assessing the Usefulness of Secondary Qualitative Data to Research Education | ReviseSociology

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities

Ethnic, socio-economic and sex inequalities in educational achievement at age 16, by Professor Steve Strand

Updated 28 April 2021

© Crown copyright 2021

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-report-of-the-commission-on-race-and-ethnic-disparities-supporting-research/ethnic-socio-economic-and-sex-inequalities-in-educational-achievement-at-age-16-by-professor-steve-strand

Ethnic, socio-economic and sex inequalities in educational achievement at age 16: An analysis of the Second Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE2) Report for the Commission on Ethnic and Racial Disparities (CRED) by Professor Steve Strand, Department of Education, University of Oxford

You can download a PDF version of this report .

This report analyses ethnic, socio-economic and sex differences in educational achievement at age 16. It uses the Second Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE2), a nationally representative sample of 9,704 students who completed GCSE examinations at the end of year 11 in summer 2015.

The LSYPE2 includes ethnic minority boosts so that sample sizes are sufficient to make robust estimates, and is the most recent dataset from which a comprehensive measure of students socio-economic status (SES) can be derived.

The analysis uses regression modelling to explore the achievement of the 9 biggest ethnic groups, at 3 levels of SES and separately for boys and girls, thus considering a total of 54 estimates for all combinations of ethnic group, SES and sex.

The key results are shown in table 1 and figure 1. The key findings are as follows:

The groups with the lowest achievement at 16 years old are White British, and Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean (MWBC) students from low SES backgrounds, who have mean scores well below the average for all students. This is most pronounced for boys (-0.77 SD and -0.68 SD respectively), but low SES girls of Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean, and White British ethnicity are also the lowest scoring groups of girls (-0.54 SD and -0.39 SD respectively).

Low SES boys of Pakistani, White Other and Any Other ethnic group also have a mean score well below the grand mean, but still score substantially higher than comparable White British and Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean boys.

Among students from average SES backgrounds, only Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean boys and White British boys have mean scores below the average for all students.

The overwhelming picture is therefore of ethnic minority advantage in relation to educational achievement at age 16. At low and average SES, no ethnic minority has a mean score substantially (less than 0.20 SD) lower than White British students, and in 23 of the 32 contrasts the ethnic minority mean is substantially (greater than 0.20 SD) above White British students of the same SES and sex.

There are only 2 instances of ethnic under-achievement compared to White British students of the same SES and sex. First, Black Caribbean and Black African boys from high SES families score lower than comparable White British high SES boys. Second, Pakistani girls from high SES backgrounds do not achieve as well as White British high SES girls, and also substantially below high SES Pakistani boys, who have the highest mean score of all groupings.

The results are discussed in relation to theories of “immigrant optimism” (Kao and Thompson, 2003), “segmented assimilation” (Portes and Zhou, 1993), and teacher expectations and cultural norms.

Table 1: Mean best 8 score by ethnic group, SES and sex, and ethnic achievement gaps relative to White British

Notes: Mean Best 8 scores show the difference between the mean score for the group and the grand mean score across all pupils (which is set to 0). Gap vs White British shows the difference in the mean score between the ethnic minority and White British students of the same sex and SES. Ethnic groups are sorted in order of the mean Best8 score for pupils of average SES.

Figure 1: Mean best 8 score by ethnic group, socio-economic status (SES) and sex

Education is the key to future life outcomes. Success in education at 16 years old is strongly predictive of later occupational, economic, health and well-being outcomes and to future social mobility: this is why 13 of the 17 social mobility indicators drawn up by the government in England are measures of educational attainment (Cabinet Office, 2011).

In the 2019 GCSE examinations, the average Attainment 8 score for Black Caribbean (39.4) and Mixed White and Black Caribbean (41.0) pupils was over 5 points lower than the average for White British pupils (46.2), or over half a grade lower in each of the 8 subjects included. At the same time, the average scores for Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Black African ethnic groups were above the White British average. What factors underpin such variation?

It is widely documented that socio-economic status (SES) is strongly implicated in low educational achievement. SES may have a direct influence, for example through poorer nutrition and an increased risk of a range of health and developmental problems, and an indirect influence through limited financial resources in the home, low parental education, reduced ability to help with homework, unemployment, maladjustment or neglect, housing instability or homelessness, greater family stress and poorer neighborhood quality in terms of services and crime (for example, Bradley and Corwyn, 2002; McLloyd, 1998; Reis, 2013; Spencer, 1996).

The greater socio-economic deprivation experienced by ethnic minority groups compared to the White ethnic group has also been well documented. For example, in England in 2016, 14% of White British pupils were eligible for a free school meal (FSM) but this doubled to 25% of Black African, 28% of Black Caribbean and 29% of Mixed White and Black Caribbean pupils (Strand and Lindorff, 2021).

This unevenness extends across many socio-economic dimensions in employment, income, housing and health (Kenway and Palmer, 2007; Strand, 2011). Ethnic minority pupils may therefore be more at risk of low achievement because of the greater socio-economic disadvantage they experience relative to White pupils.

The purpose in taking the socio-economic factors into account is not to ‘explain away’ any ethnic achievement gaps, but to better understand the root causes and therefore identify relevant policy interventions and action. For example, if ethnic achievement gaps reflect the socio-economic disparities between ethnic groups, then a focus on in-service training to address racism by secondary school teachers would be unlikely to deliver substantial change, whereas a focus on increased resourcing for disadvantaged pupils (such as the pupil premium grant) may have a greater likelihood of success.

It is therefore important that any analysis looks not just at ethnicity in isolation, but looks simultaneously at ethnicity and socio-economic status as well as gender. Previous analyses of the first Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE) have looked at these 3 factors simultaneously in relation to educational achievement at 11, 14 and 16 year old (See Strand 2011; 2012; 2014). A summary of the results at age 16 is reported in Appendix B. The results indicated average scores for ethnic minority groups were higher than for White British pupils of the same SES and sex, such that ethnic minority status was a facilitator, not a barrier, to achievement. However, the LSYPE cohort took their GCSEs in summer 2006, some time ago. This report analyses recent data from LSYPE2 which provides the most up-to-date data to analyse the combined effect of ethnicity, sex and socio-economic status in relation to students’ educational achievement at 16 year olds.

Methodology

We place the vast amount of information on the methodology in the detailed methodology, so that we can focus immediately on the key findings and discussion. We summarise here only those features that are essential to interpretation of the results and key findings. Detailed description of the dataset and analysis is also given in the detailed methodology.

The dataset

The LSYPE2 recruited a nationally representative sample of 13,000 young people aged 14 in year 9 in the 2012 to 2013 school year, and conducted detailed 45-minute interviews with them and with their parents in their own homes, as well as drawing from linked administrative sources such as the National Pupil Database (NPD).

Importantly, the LSYPE2 includes ethnic minority boosts with a target of 1,000 respondents from each of the main ethnic minority groups, so that the sample size is large enough to support robust national estimates for ethnic minority groups. The students and their families were interviewed again in wave 2 in year 10 and in wave 3 in year 11. Of the 10,396 students who completed wave 3, a total of 9,704 gave their permission for linkage to the NPD so we can analyse their GCSE results from the end of year 11 in summer 2015.

The measures

Ethnic group.

In 2019, one-third (32.9%) of the school population in England were from ethnic minority groups. We present a summary at the highest level of aggregation (White, Mixed, Asian, Black, Other) but believe there is value in a more differentiated analysis in relation to the 9 main ethnic groups in England (White British, White Other, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Asian Other, Black Caribbean, Black African and Any Other group). We include the Mixed ethnic groups in the ethnic minority part of their heritage – for example, we combine Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean students. The rationale is explained in the detailed methodology.

Socio-economic status

For descriptive purposes we focus on parental occupation as the single most frequently cited measure of social class (Raffe et al, 2006). We use the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Socio-Economic Classification (ONS-SEC), and indicative examples of the classification are given in Appendix B. We employ the dominance method (Erikson, 1984) taking either the father’s or the mother’s occupation, whichever is the highest. We do the same for parents’ educational qualifications and family income. For subsequent statistical modelling, we create a comprehensive measure of socio-economic status incorporating all 3 measures: parental occupational status, parental educational qualifications, and average family income. To do this we take the loading on the first factor of a principal component analysis of the 3 measures.

Educational outcomes

We calculate each pupil’s Best 8 point score, which is the total score across the best 8 examination results achieved by the pupil. The points are calculated on the QCA scale which is not a very familiar metric, and the score distribution is slightly negatively skewed, so for ease of interpretation we have applied a normal score transformation so the outcome is expressed in standard deviation (SD) units.

Therefore, the average score across all students is indicated by zero, and two-thirds of students score in the range between -1 and +1. For a threshold measure we report the percentage of pupils achieving a GCSE grade A* to C in both English and maths. This measure is still reported in secondary school performance tables (based on the percentage achieving a Grade 5 or above using the new 1 to 9 scale first examined from summer 2017) so is more useful than the headline measure in use in 2015, which was 5 or more GCSEs at A* to C including English and maths.

Key findings

Descriptive statistics for achievement by ethnicity, sex and ses.

Table 1 and Figure 1 presents the mean Best 8 points score and the percentage achieving GCSE A* to C in both English and mathematics by ethnicity, sex and 3 measures of SES (parental occupation, parental education and family income).

The key points are as follows.

At the highest level of ethnic aggregation, the mean Best 8 score was 0.05 for White students and -0.06 for Black students, giving a Black-White difference of -0.11 SD. This Black-White gap is statistically significant but small. By way of comparison, Cohen’s (1988) effect size thresholds suggest 0.20 SD is small, 0.50 SD is medium and 0.80 is large.

The results contrast strongly with those from the US, where in the 2017 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), Black students scored -0.81, -0.83 and -0.89 SD below the mean for White students in mathematics at age 10, 14 and 18 respectively. They also scored approximately -0.72 SD below the mean for White students for reading at the same ages (US Department of Education, 2019).

When the ‘Black’, ’Asian’ and ‘White’ groups are disaggregated, some slightly larger gaps are found. However, the only ethnic group with an average score significantly below the White British mean is Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean students, with a gap of -0.29 SD, while Black African and Mixed White and Black African students have a mean score near identical to White British. All other ethnic groups score as well as, or in the case of Indian and Asian Other ethnic groups significantly better than, the White British average.

This Black Caribbean achievement gap is the same magnitude as the gender gap which is also 0.29 SD, with girls scoring higher than boys. However, both gaps are dwarfed by the parental occupation gap, which is over 3 times larger at 0.97 SD. The family income gap is 0.93 SD and the parental education gap is 1.14 SD.

If we take a conservative analysis, comparing the results for the 22% of students in the lowest 3 parental occupational groups (LTU, routine and semi-routine occupations) against the average for the 45% of students with a parent in the highest groupings (higher technical, higher managerial and professional occupations), the gap is 0.81 SD, still 3 times larger than either the Black Caribbean or gender gaps.

Table 2: KS4 results by ethnicity, sex and parental SEC

Notes: SEC is the ONS Socio-economic classification (SEC) of the occupation of the highest classified parent. Parent Educ. is the highest educational qualification held by the most qualified parent. Family income is average family income expressed in quintiles.

Figure 2: Mean Best 8 points score by ethnic group, sex and parental SEC

Figure 3: mean best 8 points score by ethnic group, sex and parental sec, ethnicity and socio-economic status (ses).

Considering the 3 factors of ethnic group, sex and SES separately is limited, because there is significant confounding between these variables. Most particularly, levels of socio-economic disadvantage are substantially higher among ethnic minority groups than among the White British majority. Table xxx presents averages for a wide range of socio-economic measures separately for each ethnic group.

The key findings are:

Parental occupation (r= 0.38), parental education (r= 0.38) and family income (r= 0.38) were all positively correlated with KS4 Best 8 score, but the overall SES measure gave the highest correlation (r= 0.45). Therefore, SES is the best single measure in relation to exam success.

In terms of SES, White British (0.22 SD), Indian (0.21 SD) and Asian Other (0.11 SD) had mean SES scores above average, Black Caribbean (-0.15 SD), Black African (-0.12 SD) and White Other (-0.14 SD) were closely grouped, while Pakistani (-0.53 SD) and Bangladeshi (-0.83 SD) had substantially the lowest SES.

The gaps in the underlying measures are often stark:

- for 20% of White British students the highest parent occupation is ‘LTU, routine or routine occupation’, but this more than doubles to over 40% for each of the Black African, Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic groups

- for 29% of White British students at least one parent has a degree, compared to Black African (40%), Indian (43%) and Asian Other (52%) students, but just 13% of Bangladeshi students

- White British students had the highest annualised family income (£40,785), followed by Indian (£36,246) and Asian Other (£33,862), but is more than one-third lower for Black Caribbean (£29,485) and Black African (£28,405) students, and half as high for Pakistani (£22,693) and Bangladeshi (£19,828) students

- 24% of White British students have been entitled to a free school meal at some time in the last 6 years, but this is more than doubled for Black Caribbean (47%), Any Other (49%), Black African (53%) and Bangladeshi (61%) students

While Black Caribbean and Black African students had similar overall SES (-0.15 and -0.12 respectively), they differed in their profile across the 3 underlying components: Black African students have a higher proportion of parents in ‘LTU, routine or semi-routine’ occupations (41% vs. 31%) and slightly lower family annualised income (£28,405 vs. £29,475), but had a higher proportion of parents educated to degree level (40% vs. 23% respectively).

Table 3: socio-economic variation between ethnic groups

You may need to scroll horizontally to see all columns.

Notes. ‘SES’ is a standardised score of the loading on the first factor from a principal components analysis of parental occupation, parental education and average family income. ‘Parental occupation’ as coded by the ONS Socio-Economic Classification (ONS-SEC) 3 category version. ‘LTU’ means long term unemployed, defined as 6 months or more. ‘Parental education’ is the highest qualification assessed on a 7 point scale ranging from no educational qualifications through to university degree. ‘Family income’ is average equivalised income per annum. ‘FSM’ indicates eligibility for free school meals in January of year 11. ‘EVER6’ indicates entitlement to free school meals at any point during the last 6 years (Y6-Y11). ‘IDACI’ is the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index quartile, based on the proportion of children in the neighbourhood from families entitled to state benefits. ‘X’ indicates fewer than 10 cases in the cell so the value is suppressed following ONS rules.

Interactive effects of ethnicity, sex and SES with achievement

Given these results, we complete a regression analysis to look at the combined associations of achievement with ethnicity, sex and SES. There were several highly significant ethnic and SES interactions, one ethnic and sex interaction and a 3-way ethnic, SES and sex interaction. Therefore, a full-factorial model was specified and effects were assessed using estimated marginal means. The parameters from the model are given in Appendix C.

Table 3 and Figure 4 present the mean Best 8 score for each ethnic, SES and sex combination, along with the ethnic achievement gap showing the difference between the average score for the ethnic minority compared to White British pupils of the same sex and SES.

The key findings are as follows.

Mean Best 8 score

The groups with the lowest achievement at age 16 are White British, and Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean students from low SES backgrounds, who are scoring substantially below the average for all students (which is set at zero). This is most pronounced for boys (-0.77 SD and -0.68 SD respectively), but low SES girls in the Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean, and White British ethnic groups are also the lowest scoring groups of girls (-0.54 SD and -0.39 SD respectively).

Low SES boys in the Pakistani, White Other and Any Other ethnic groups also score well below the mean, but still score substantially higher than comparable White British, and Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean peers.

Among students from average SES backgrounds, only Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean boys and White British boys score below the grand mean.

Beyond the above, no ethnic, SES and sex combination scores substantially below the grand mean, with the majority scoring well above the average.

Ethnic gaps relative to White British

The overwhelming picture is that ethnic minority groups have higher educational achievement at age 16 than White British students of the same sex and SES. This is particularly notable at low and average SES, where no ethnic minority groups have a significantly lower score than White British students, and indeed in 23 of the 32 comparisons the mean score for ethnic minority students is substantially higher than for comparable White British students.

There are only 2 instances of ethnic under-achievement compared to White British students of the same SES and sex. First, Black Caribbean and Black African boys from high SES families score more than 0.20 SD lower than comparable White British boys. Second, Pakistani girls from high SES backgrounds do not achieve as well as White British high SES girls, and substantially below high SES Pakistani boys, who have the highest mean score of all groupings.

Table 4: Mean best 8 score by ethnic group, SES and sex, and ethnic achievement gaps relative to White British

Figure 4: mean best 8 score by ethnic group, level of ses and sex, ethnicity and low educational achievement.

The key finding is that White British and Black Caribbean students, both boys and girls, from low SES backgrounds are the lowest achieving groups of all students. While low SES boys from Pakistani, White Other and Any Other ethnic groups also score below the overall average, they are still scoring significantly higher than White British and Black Caribbean low SES boys. It is also notable that at mean SES, it is again only White British and Black Caribbean boys who score substantially below the average. A key question therefore is why most ethnic minority groups are so much more resilient compared to White British and Black Caribbean students.

The ‘immigrant paradigm’ (Kao and Thompson, 2003) suggests that recent immigrants devote themselves more to education than the native population because they lack financial capital and see education as a way out of poverty. In a similar vein, Ogbu (1978) makes a distinction between ‘voluntary minorities’ (such as immigrant groups who may be recent arrivals to the country and have very high educational aspirations) and ‘involuntary’ or ‘caste like’ minorities (such as African Americans or Black Caribbean and White working class pupils in England) who hold less optimistic views around social mobility and the transformative possibilities of education.

This theory can, for example, account for the substantial contrast between Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean pupils on the one hand and Black African and Mixed White and Black African pupils on the other, whose achievement is substantially higher despite the same or higher levels of risk in terms of low SES, neighbourhood deprivation, and poverty. Most Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean pupils are third generation UK born, while many Black African pupils are more recent immigrants, some of whom have arrived directly from abroad. For example, the 2011 national population Census indicates that one-third (66.7%) of the Black African population were born outside of the UK, compared to 39.8% of the Black Caribbean population (ONS, 2013).

But if ‘immigrant optimism’ is the explanation, why does the achievement of Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean students more closely match that of White British students, particularly at low SES, rather than matching other ethnic minority groups? Partly this may be because they are one of the longer-standing migrant groups, with the largest waves of migration in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Ogbu (1978) suggests that those minorities who have been longest established in a country, particularly in a disadvantaged context, may be the least likely to be optimistic about the possibilities of education to transform their lives, and several studies have noted this ‘second generation’ gap (for example, Rothon et al, 2009). But Indian and Pakistani migration was also high during the 1950s and 1960s, why is the achievement profile for these ethnic groups not also closer to White British students?

Perhaps relevant here is “selective assimilation theory”. Black Caribbean migrants in the 1960’s predominantly moved into poor urban and inner city areas populated by the White British working class. The intersecting of the communities is reflected in the high level of inter-ethnic partnerships and births, with there now more being students in school from the Mixed White and Black Caribbean ethnic group than there are from the Black Caribbean ethnic group (1.6% vs. 1.1% of the school population) (DfE, 2019). Thus, Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean students may have cultural attitudes that parallel their (predominantly) White British working class neighbours.

In contrast, other long standing ethnic minority groups have different patterns of migration. Indian migrants were more likely to be of high SES in their host countries, many were professionals and managers, and migrated to a more varied and diverse selection of geographical areas. Other groups such as Pakistani migrants, while also tending to move predominantly to poor areas of inner cities where housing was cheap, tended to have higher levels of ethnic segregation, retaining greater cultural homogeneity.

The most direct support for the ‘immigrant optimism’ thesis comes from Strand (2011; 2014), in his analysis of the original LYSPE, which identified 4 key factors underlying the greater resilience of low SES ethnic minority pupils:

- high educational aspirations on the part of students to continue in education post-16 and to attend university, placing education in central role for achieving their future goals

- high educational aspirations by parents and strong ‘academic press’ at home

- high levels of motivation and homework completion

- strong academic self-concept

There is insufficient time to undertake further analysis at present before the deadline for this report, but further analysis will be completed later in the year to see if these results from LSYPE are replicated for LSYPE2.

Ethnic minority underachievement

The overwhelming picture is that ethnic minority groups have higher average levels of achievement than White British peers of the same SES and sex. While they were very much exceptions to the rule, there were 2 specific instances of ethnic under-achievement.

First, Black Caribbean and Black African boys from high SES homes underachieved relative to White British high SES boys. What underlies this particular finding is not known, and worthy of further investigation. Previous research has indicated that Black Caribbean pupils are under-represented by their teachers in entry to higher tier examinations, after a wide range of controls for prior attainment, SES, attitudes and behaviour (Strand, 2012), and that Black Caribbean and Mixed White and Black Caribbean pupils are more often subject to disciplinary sanctions like exclusion than other ethnic groups, again after control for covariates (Strand and Fletcher, 2014).

It may be that in school settings, negative expectations about Black boys lead to greater surveillance and pre-emptive disciplining by teachers, which may be particularly disproportionately felt by Black middle class boys (Gillborn et al, 2012). Alternatively, it may be that White British middle class families use their financial resources to purchase advantages, like private schooling, to a greater extent than Black middle class families. In the LSYPE2 we found 6.7% of White compared to 2.2% of Black pupils attended independent schools, although analysis of the British Social Attitudes survey suggests no significant difference (Evans and Tilley, 2012).

Out of school factors may also be influential. For example, Foster et al. (1996) and Sewell (2009) argue that Black boys experience considerable pressure by their peers to adopt the norms of an ‘urban’ or ‘street’ subculture where more prestige is given to unruly behaviour with teachers than to high achievement or effort to succeed (for example, Foster et al., 1996; Sewell, 2009). Gangster culture and hyper-masculinity may be shared to greater extent by White and Black boys within working class contexts, more so than in middle class spaces. Issues of identity could also be felt particularly by Black middle class boys, with some researchers suggesting Black middle-class families often express “an unease about middleclassness which was viewed by some as a White social category” (Ball et al, 2013, p270, see also Archer, 2010; 2011). Of course, these arguments are not mutually exclusive, both in-school and out-of-school factors may well play a role.

Second, Pakistani high SES girls underachieved compared both to White British high SES girls, and indeed achieved less well than high SES Pakistani boys. It may be that traditional attitudes to gender roles, lower perceived benefits of daughters’ relative to sons’ education, and threats to respectability and modesty expressed by parents in Pakistan (Purewal and Hashmi, 2015) also apply in England. However, Fleischmann and Kristen (2014) looking at second generation immigrants in 9 European countries (including England and Wales) indicate that gender gaps favouring males in countries of origin are largely reversed in the second generation, transforming to the patterns of female achievement advantage seen in the host countries. This is a small group within the LSYPE2 dataset, because of the very skewed SES distribution for Bangladeshi and Pakistani students. For example, the number of Pakistani pupils in the top top 20% of SES is just 17 and fewer than 10 Bangladeshi pupils (the comparable figure for White British pupils is 1667 cases). The finding should therefore be treated with caution, but is worthy of further investigation.

These results indicate that ethnic minority groups on average achieve higher levels of success in education at age 16 than White British pupils. To the extent that there is a small gap for Black Caribbean students, this seems to reflect structural inequality in SES, with fewer parents in managerial and professional roles and lower average family income. Gaps in achievement at age 16 related to SES are large and persistent, and represent by far the greatest challenge to equity and social mobility agendas.

Educational achievement at age 16 is crucial, in that it acts as a gatekeeper to higher education and employment opportunities later in life. Nevertheless, ethnic variation in outcomes at later ages still remains. For example, in access to high-tariff universities (Boliver, 2016), in entry to work (Heath and Di Stasio, 2019) and to the highest occupational groups (UK Government, 2020).

Detailed methodology

Ethnic minority groups.

Table xxx indicates the unweighted number of pupils within each ethnic group as recorded in the LSYPE2 wave 3 dataset and with valid linkage to the NPD. The third column of the table shows the percentage that each ethnic group represents in the whole school population, sourced from the 2019 school census. This shows that one-third of the school population in England (32.9%) are from an ethnic minority group (DfE, 2019).

Table 5: Ethnic coding for purposes of analysis of LSYPE2

Table 5(a): full set of ethnic codes, table 5(b): ethnic groups used in the analysis.

Notes: (a) less than 10 pupils so number suppressed.

In analysing the LSYPE2 data, a balance needed to be struck between the number of ethnic groups, the size of these groups in the school population and the number of cases in the specific LSYPE2 sample.

The largest ethnic minority groups (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black African, Black Caribbean, White Other and Asian Other) were retained.

The Mixed ethnic groups have been shown to be extremely heterogenous with little in common in terms of the achievement profile among the sub-groups (see Strand, 2015). In term of their achievement profile, there is greater similarity with the ethnic minority side of their Mixed ethnicity. For example, the achievement of Mixed White and Black Caribbean pupils is similar to that of Black Caribbean pupils, the achievement of Mixed White and Black African pupils is similar to the Black African, and the achievement of Mixed White and Asian (MWAS) pupils is similar to that of Asian Other pupils. This is shown in Figure xxx, which is drawn from Strand (2015), p32.

Source: Strand (2015). ‘Ethnicity, deprivation and educational achievement at age 16 in England: trends over time.’ DfE Research Report 439B, p32.

Therefore, to more accurately reflect the patterns of achievement, and to maximise the analytic samples, the Mixed ethnic groups were included with the relevant ethnic minority group.

Smaller ethnic groups were merged. Thus, White Irish and Gypsy Roma Travellers (GRT) were included in White Other; Chinese were included in Asian Other and MWAS; and Black Other and Mixed Other groups were included in Any Other ethnic group.

Table 5(b) shows the 9 ethnic groups used for this analysis, the unweighted number of cases in each group and the percentage the groups represent in the whole school population (school census 2019).

Family socio-economic classification (SEC)

We utilised the ONS Socio-Economic Classification (SEC). A family SEC variable is included in LSYPE2 based upon the household reference person (HRP), but in a large number of cases the HRP was not interviewed (n=487) or the individual was not classifiable (n=121). We therefore created our own family SEC measure. First, we took the SEC for the main parent, which had fewer missing or unclassifiable instances (n=116). Second, to create a family measure, we substituted the SEC of the second parent (if present) if it was higher than for the main parent. As a robustness check we completed the same process taking the highest of the mother’s or father’s SEC. This measure was very highly correlated (r=0.996) with the MP/SP version, but the MP/SP version had fewer missing cases (n=116 as opposed to n=502) so was preferred.

Table 6: ONS Socio-economic classification (SEC) categories: LSYPE2 Sample

We also looked in wave 2 and wave 3 for SOC2010 values if there was no SEC record in the wave 1 file. These employ 9 major groups and 25 sub-major groups (see SOC2010 volume 1: structure and descriptions of unit groups ). We converted codes between SOC2000 and SOC2010 where needed (see https://www.bls.gov/soc/soc_2000_to_2010_crosswalk.xls ). We were able to find valid values for all but 33 cases.

Parental educational qualifications

We took the highest educational qualification of the main parent, substituting the highest qualification of the second parent (where present) if it was higher, termed the dominance method (Erikson, 1984). If we could not find a value in the wave 1 file we again sourced the variable from the wave 2 or wave 3 file. We were able to find valid values for all but 27 cases. A small number of cases (n=37) which were coded as ‘entry level qualifications’ were combined with ‘Other qualifications’. This created a 7 point scale ranging from ‘No educational qualifications’ through to ‘Degree or equivalent’. Descriptive statistics showing the relationship with student achievement are given in Table 1.

Family income

Household income is based on a survey response, with respondents picking a band from a list to represent the annual household income from all sources. The results have been edited to take account of implausible responses, primarily through the use of self-reported earnings data.

Earnings data was generally more credible, not least because parents reported their own earnings, over the time period of their choice, rather than having to combine sources and annualise the results. This data has also been edited where implausible, such as where what looked like an annual salary for the stated occupation was reported as being paid weekly.

Where the plausible earnings of a household were greater than the annual income selected, the earnings have been used instead. This is likely to underestimate the true income, as it excludes other sources such as benefits, but should still represent an improvement on the self-reported estimate.

The data was collected in 15 bands allowing a high degree of differentiation. For descriptive purposes we used the midpoint of the ranges as the data value rather than the band number to give a mean income in pounds per annum. It should be noted that income data is notoriously difficult to collect accurately via household surveys, and LSYPE2 is no exception, with a high level of non-response. To deal with this, we took the average income over all 3 waves of the LSYPE2, this reduced the missing cases to n=437 (or 4.5%) of our sample. To avoid losing these cases, we imputed the value predicted from a regression of income on other variables closely related to income (entitlement to a FSM, IDACI score and parental SEC), so only had one missing value in the final analysis.

Income deprivation affecting children index (IDACI)

IDACI is produced by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. The index is based on 32,482 super output areas (SOAs) in England, which are geographical regions of around 1,500 residents, designed to include those of similar social backgrounds.

The IDACI score is the percentage of under-16s in the SOA living in income deprived households (primarily defined by being in receipt of certain benefits). This variable is highly skewed and so for the purpose of the current analysis the measure was normal score transformed to give a variable with a mean of 0 and SD=1. A score above 0 indicate greater than average deprivation, and score below 0 indicate less than average deprivation, relative to the average for the LSYPE2 sample. Both 2001 and 2007 IDACI measures were included in the LSYPE2 file. The means of the 2 were nearly identical (24.7% and 25.7%) and they correlated r=0.97, so the more recent 2007 values were used. You can see more information about IDACI .

FSM and EVER6

We took from the January census of year 11 whether the pupil was entitled to a free school meal (FSM) or had ever been entitled over the last 6 years (EVER6).

The LSYPE2 sample

The primary sample frame for LSYPE2 was the England school census, which was used to identify sample members in state-funded education. This provides access to pupil-level characteristics information about these young people, which was used to stratify the sample.

The stratification has been designed to maintain minimum numbers in certain subgroups of interest right through to the planned end of the survey, to ensure robust analyses of these groups can continue. These subgroups include those with free school meals, those with special educational needs (SEN), and certain ethnic groups. The sample also included pupils from independent schools and pupil referral units (PRUs), these schools and settings were sampled first and then asked to supply contact details for pupils.

Interviews took place with both the young person and at least one parent in the first 3 waves (until the young person was 15 or 16 years old). In wave 1 the interviews took place over a 5-month period, starting in early April 2013 and finishing in early September 2013. In wave 1 LSYPE2 achieved a response rate of 71%, representing an achieved sample of 13,100.

The analytic sample

As stated, there were 13,100 responding young people in wave 1 of LSYPE2. Of these, 12,152 responded in wave 2 and 10,396 in wave 3. Of those responding in wave 3, a total of 9,307 gave permission for linkage and were matched to results in the NPD. Some of those giving permission were in independent schools (n=410) who were missed by the DfE in the initial data match, and so are not yet included in our analysis (at 18/12/20). 9.307 was the total sample available, and we had complete observations for ethnic group and sex, but a small number of cases that were missing parental SEC (n=49), parental education (n=22), family income (n=26), SES (n=69), entitlement to a FSM/EVER6 (n=17) or IDACI (n=7), had to be excluded on a pairwise basis. The ONS-SRS does not have the SPSS Missing Values module, so we cannot impute missing values for these cases, but we will explore whether this might be possible through other means at a later date.

Approach to analysis

We were primarily interested in the relationship between variables, not in simply recapturing descriptive statistics for the relevant population. In these cases, the use of weights is sometimes argued to be problematic (Solon, Haider and Woodridge, 2015). However, given the extent of attrition from wave 1 to wave 3 of LSYPE2, we considered it important to use weights that are meant to limit the effect of differential attrition, and used the combined design and non-response scaled sampling weights from wave 3 in all analyses (LSYPE2_W3_Weight_scaled).

The ONS-SRS has not purchased the SPSS Complex Samples module, and so, despite the software being available to university staff and students throughout the country, we were not able to use it to simultaneously account for weight and for clustering at the school level.

However, we also ran all our models using a complex survey design using the svydesign() and svyglm() functions contained within version 3.35-1 of the Survey package (Lumley, 2019) in version 3.6.1 of R (R Core Team, 2019). These models used the students’ KS4 school URN as the cluster ID and the LPYSE2_W3_Weight_scaled as the sampling weight. In all cases there were no substantive differences in results, means were near identical. Although SEs tended to be marginally higher, all results that were statistically significant in our SPSS regressions were also significant in the R versions. Therefore, we do not consider this a problem for the analysis.

Archer, L. (2010). ‘We raised it with the Head’: the educational practices of minority ethnic, middle-class families. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(4), 449 to 469.

Archer, L. (2011). Constructing Minority Ethnic Middle-class Identity: An Exploratory Study with Parents, Pupils and Young Professionals. Sociology, 45(1), 134 to 151. doi:10.1177/0038038510387187

Ball, S. J., Rollock, N., Vincent, C., and Gillborn, D. (2013). Social mix, schooling and intersectionality: identity and risk for Black middle class families. Research Papers in Education, 28(3), 265 to 288. doi:10.1080/02671522.2011.641998

Boliver, V. (2016). Exploring Ethnic Inequalities in Admission to Russell Group Universities. Sociology, 50(2), 247 to 266. doi:10.1177/0038038515575859

Bradley, R. H., and Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371 to 399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Cabinet Office (2009). Unleashing aspirations: The final report of the panel on fair access to the professions . London: Cabinet Office.

Cabinet Office (2011). Opening Doors, Breaking Barriers: A Strategy for Social Mobility. London: Cabinet Office.

Cabinet Office (2017). Race Disparity Audit: Summary findings from the Ethnicity facts and figures website. London: Cabinet Office.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd Edition). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

DfE (2019). Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2019 . London: Department for Education.

DfE (2020). Key stage 4 performance, 2019 (Revised) . London: Department for Education.

DfE (2020). Secondary accountability measures: Guide for maintained secondary schools, academies and free schools . London: Department for Education.

Erikson, R. (1984). Social class of men, women and families. Sociology, 18, 500 to 514.

Evans, G., and J., T. (2012). Private schools and public divisions: the influence of fee-paying education on social attitudes . British Social Attitudes, 28th Report.

Foster, P., Gomm, R., and Hammersley, M. (1996). Constructing educational inequality. London: Falmer Press.

Gillborn, D., Rollock, N., Vincent, C., and Ball, S. J. (2012). ‘You got a pass, so what more do you want?’: race, class and gender intersections in the educational experiences of the Black middle class. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15(1), 121 to 139. doi:10.1080/13613324.2012.638869.

Heath, A. F., and Di Stasio, V. (2019). Racial discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: a meta-analysis of field experiments on racial discrimination in the British labour market. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(5), 1774 to 1798. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12676

Kao, G., and Thompson, J. S. (2003). Racial and ethnic stratification in educational achievement and attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 417 to 442. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100019

Lumley, T. (2019) ‘Survey: analysis of complex survey samples’. R package version 3.35-1.

McLoyd, V. C. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist 53(2), 185 to 203. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2013). DC2205EW – Country of birth by ethnic group by sex . Office for National Statistics.

Portes, A., and Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530(1), 74 to 96. doi:10.1177/0002716293530001006

Purewal, N., and Hashmi, N. (2015). Between returns and respectability: parental attitudes towards girls’ education in rural Punjab, Pakistan. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 36(7), 977 to 995. doi:10.1080/01425692.2014.883274

R Core Team (2019) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, URL https://www.R-project.org

Raffe, D., Croxford, L., Iannelli, C., Shapira, M., and Howieson, C. (2006). Social-Class Inequalities in Education in England and Scotland, CES Briefing No. 40 . Centre for Educational Sociology, University of Edinburgh.

Reiss, F. (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 90, 24 to 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026

Rothon, C., Heath, A., and Lessard-Phillips, L. (2009). The Educational Attainments of the “Second Generation”: A Comparative Study of Britain, Canada, and the United States. Teachers College Record, 111(6), 1404 to 1443.

Sewell, T. (2009). Generating Genius: Black Boys in Search of Love, Ritual and Schooling. Stoke on Trent: Trentham books.

Spencer, N. (1996). Poverty and child health. Medical Press.

Strand, S. (2011). The limits of social class in explaining ethnic gaps in educational attainment. British Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 197 to 229. 10.1080/01411920903540664.

Strand, S. (2014). Ethnicity, gender, social class and achievement gaps at age 16: intersectionality and ‘getting it’ for the white working class. Research Papers in Education, 29(2), 131 to 171. 10.1080/02671522.2013.767370.

Strand, S. (2015). Ethnicity, deprivation and educational achievement at age 16 in England: Trends over time (DfE Research Report 439B) . London: Department for Education.

UK Government (2020). Ethnicity fact and figures service, work, pay and benefits: Employment by occupation - GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures.

US Department of Education (2019). National Centre for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Retrieved from the Main NAEP Data Explorer . (Table prepared October 2019).

Appendix A: Age 16 points score by ethnic group, gender and SES from LSYPE (Strand, 2014)

The KS4 exam results for all pupils in England are available as part of the National Pupil Database (NPD), but there is only very limited data on socio-economic status (SES). The NPD contains only a single measure of SES sourced directly from the pupil, which is whether the pupil is, or is not, entitled to a free school meal (FSM), or whether they have ever been entitled to a FSM at some time in the last 6 years (EVER6). There are often criticisms that some pupils do not claim a FSM even if entitled because of the stigma, but perhaps more problematic is that a simple binary measure tells us nothing about the huge differences in home circumstances among the 85% of pupils who are not entitled to a FSM, which can range from families only just over the income threshold for FSM to those from extremely well-off circumstances.

Fortunately, there is good data on both ethnicity and SES is some of the England longitudinal datasets. For example, Strand (2014) used the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE) to draw on data on parents’ occupational classification, their educational qualifications, whether they owned their own home, the deprivation of the neighbourhood in which they lived as well as whether the student was entitled to a FSM, in order to create a robust and differentiated measure of the family socio-economic status (SES). The LSYPE also includes ethnic minority boosts with a target of 1,000 respondents from each of the main ethnic minority groups, so that the sample size is large enough to support robust national estimates for ethnic minority groups.

The results of the analysis are presented below.

Notes: (1). The outcome (total points score) was drawn from examinations completed in 2006, and is a measure of achievement based on all examinations completed by the young person at age 16, expressed on a scale where 0 is the mean (average) score for all Young People at age 16 and two-thirds of YP score between -1 and 1. (2). The SES measure also has a mean (average) of zero and the effects for low SES are estimated at -1SD and of high SES at +1SD. Source: See Strand (2014) for full details.

Appendix B: Indicative examples of professions in the ONS statistics socio-economic classification (ONS-SEC)

Table 7: indicative examples of professions in each reduced ns-sec class.

Table source: Office for National Statistics

Long Term Unemployed (LTU) are defined as those who have been out of work for 6 months or longer and are included as an eighth category.

Most recently this has been highlighted in the Government’s Racial Disparity Audit (RDA), as reported on the government’s Ethnicity fact and figures website. Black African pupils are 3 times more likely than White British pupils to be entitled to a free school meal, Black Caribbean pupils are 3 times more likely to live in persistent poverty than White British pupils, pupils in the Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic groups are more likely than other groups to live in the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods, and so on (for example, Strand, 2011).

Appendix C: Full factorial regression of Best8 score: regression coefficients and parameters

Notes: Estimated with adjustments for LSYPE3 weights and clustering at the school level.

Is this page useful?

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

Beta This is a new service – your feedback will help us to improve it.

- School workforce in England

Correction to vacancy section of School level summary within Additional supporting files.

Correction to the historical data in parliamentary constituency files.

Teacher characteristics at school level and school level summary added as supporting files. School level support staff updated with additional indicators.

Introduction

This release is largely based on the School Workforce Census (SWC). The census, which runs each November, collects information from schools and local authorities on the school workforce in state-funded schools in England.

Independent schools, non-maintained special schools, sixth-form colleges and further education establishments are not included in the SWC.

This release includes information on teaching and support staff, their characteristics, teacher retention and pay, qualifications and details of the subjects taught in secondary schools.

We present some breakdowns of this data in the text below, and more detail is available via the table tool or downloading the data files.

This year alternative estimates of teacher pay have been published as ad hoc statistics in Median teacher pay using teacher pension scheme (TPS) data . This uses TPS data which is retrospectively updated with any pay decisions that were backdated to before the census date in November each year. It is intended to provide an estimate that is more representative of teachers' pay after the award is fully implemented.

Quick links

Related information, data guidance.

- Pre-release access list

Releases in this series

- Reporting year 2022

- Reporting year 2021

- Reporting year 2020

- Reporting year 2019

- Reporting Year 2018

- Reporting Year 2017

- Reporting Year 2016

- Reporting Year 2015

- Reporting Year 2014

- Reporting Year 2013

- Reporting Year 2012

- Reporting Year 2011

- Reporting Year 2010 (November)

- Reporting Year 2010 (January)

Methodologies

Headline facts and figures - 2023, fte of all workforce.

5 in 10 are teachers, 3 in 10 teaching assistants, 2 in 10 other support staff

FTE = Full-time equivalent

FTE of all teachers

300 more than 2022

FTE of teaching assistants

1,800 more than in 2022

Pupil to teacher ratio

20.8 primary & nursery, 16.8 secondary, 6.5 special & PRU

The FTE number of pupils divided by the FTE number teachers (qualified and unqualified)

FTE number of entrants

3,900 fewer than 2022

FTE = Full time equivalent of qualified teachers

FTE number of leavers

400 fewer than 2022

FTE = Full time equivalent qualified teachers.

Average salary of teachers

Median = If you were to put all teacher salaries in order, this is the salary in the middle of that list

Teacher vacancy rate

6 per thousand teachers in service

Full and part-time vacancies

Percentage of hours taught by a specialist teacher

Percentage of EBacc hours that were taught by a teacher with a relevant post-A level qualification in secondary schools

EBacc = English Baccalaureate. This includes English, sciences, mathematics, geography and history.

- There are 468,700 FTE teachers , which is an increase of 300 since last year and an increase of 27,300 since 2010 when the school workforce census began.

- There are 282,900 FTE teaching assistants , which is an increase of 1,800 since last year and an increase of 61,400 since 2011 when the census began collecting support staff information.

- Pupil to teacher ratios are similar to last year : 20.8 pupils per teacher in nurseries and primary schools (up 0.1 on last year), 16.8 in secondary schools (no change) and 6.5 in special and PRU schools (up 0.1).

- The number of teachers entering and leaving service both fell though the number of entrants continues to be higher than for leavers. This, combined with changes in working patterns and an increase in unqualified teachers, resulted in a marginal increase to the number of teachers in England.

- Almost 9 in 10 teachers remain teaching in state-funded schools in England one year after qualification.

- 3 in 5 teaching hours were spent teaching English Baccalaureate (EBacc) subjects. Almost 9 in 10 of these hours were taught by a teacher with a relevant post-A level qualification.

- Teacher vacancies have increased by 20% to 2,800 in November 2023 from 2,300 in November 2022, and more than doubled in the last three years from 1,100 in November 2020. Temporarily filled posts also increased ; from 2,100 to 3,700 over three years.

Explore data and files used in this release

View or create your own tables.

View tables that we have built for you, or create your own tables from open data using our table tool

Data catalogue

Browse and download open data files from this release in our data catalogue

Learn more about the data files used in this release using our online guidance

Download all data (ZIP)

Download all data available in this release as a compressed ZIP file

Additional supporting files

All supporting files from this release are listed for individual download below:

Qualification subjects mapping (xlsx, 96 Kb)

Subject of teacher qualifications mapped to grouped subjects used to identify specialist teachers with qualification related to the subject they are teaching.

School level summary file (xlsx, 8 Mb)

Data at school level, including details on geography, characteristics, pay, absences, and vacancies.

Support staff characteristics - school level time series (zip, 40 Mb)

Support staff characteristics at school level for census years 2011 to 2023

Teacher characteristics - school level time series (zip, 58 Mb)

Teacher characteristics at school level for census years 2010 to 2023

The size of the school workforce

Within this section we primarily discuss full-time equivalent (FTE) as opposed to headcounts. FTE best reflects the varied working patterns that the workforce may have.

As at November 2023 (2023/24), 979,100 FTE staff were working in state-funded schools in England. Of these, nearly half (48%) were teachers.

The FTE number of teachers increased marginally to 468,700 in 2023/24. This is an increase of 300 (<0.1%) from last year, and an increase of 27,300 (6%) since 2010/11. Headcount of teachers also increased; by 1,900 to 513,900 in the latest year.

Most teachers held qualified teacher status (97%), the same as previous years. Teachers may be undertaking further qualifications during their employment to gain qualified teacher status.

The type of school in which teachers worked was split evenly between nurseries/primary and secondary schools; 47% (218,500) of teachers worked in nurseries and primary schools, 46% (217,600) in secondary schools, 6% (28,200) in special schools and state-funded alternative provision schools including PRUs. 1% (4,400) were centrally employed by a local authority.

Further information on numbers of teachers in the UK, including non-maintained schools in England, can be found in the Education and Training Statistics for the UK accredited official statistics.

Support staff

Support staff are categorised into posts of teaching assistants, administrative staff, auxiliary staff, technicians and other supporting staff, plus two new posts of school business professional and leadership non-teacher reported for the first time in 2023/24. School business professionals include roles such as bursar, business manager, finance officer, office manager, premises manager or ICT network manager. Leadership non-teachers are members of the school's senior leadership team who are not reported in a teaching post. These new posts have displaced reporting from other posts, particularly administrative staff.

The FTE of support staff has increased each year since 2019/20, to 510,400 in 2023/24, and has now passed the previous peak of 2015/16. This is an increase of 4,800 (0.9%) since last year. This increase is mainly due to an increase of 2,400 in other support staff.

More support staff work part-time than is the case for teachers, this results in very different numbers for FTE and headcount. Approximately 5 in 10 technicians, 6 in 10 administrative staff and other school support staff, 8 in 10 teaching assistants, and 9 in 10 auxiliary staff work part time.

Two thirds (66%) of teaching assistants work in primary schools, and 16% work in special schools and pupil referral units. The majority of technicians work in secondary schools, 92%.

Information on support staff was collected in the school workforce census for the first time in 2011/12. Please follow this link to FTE for support staff by role .

Occasional teachers and third party support staff

The school workforce census does not identify supply teachers or support staff. However, teachers and support staff who are not directly employed by the school or local authority and who are in school on census day (early November each year) with a contract or service agreement lasting fewer than 28 days are recorded as ‘occasional’ teachers and ‘third party support staff’ respectively.

In November 2023, schools reported 15,777 occasional teachers (headcount) on census day. This is down from the previous year when 16,594 were reported. Their headcount by Qualified Teacher Status is available in the data catalogue for each individual school.

In November 2023, schools reported 48,476 third party support staff (headcount) on census day. This is down from the previous year when 49,420 were reported. Their headcount by post is available in the data catalogue for each individual school.

Educational Psychologists

The school workforce census asks local authorities to report the number of educational psychologists they employ. This does not include where the service has been outsourced or shared between local authorities. For information on the data collection and limitations, please see this publication’s methodology. The headcount and FTE of these educational psychologists, by local authority, is available in the data catalogue.

In November 2023, local authorities reported employing 2,546 educational psychologists (2,102 FTE) on census day. This is slightly up on the previous year, 2,325 (1,939 FTE). Data by local authority and working pattern is available to download from the data catalogue.

Teacher characteristics

This section presents key teacher characteristics. Further breakdowns of teacher characteristics (such as by grade, school phase, qualified teacher status and working pattern) are available to download from the data catalogue, or you can create your own tables in our table tool via the green ‘Explore data’ buttons. We discuss headcount in this section, rather than FTE. This is so that we can consider the characteristics of the workforce without differences in working pattern influencing the figures.

Gender makeup of the teaching workforce is consistent over time and is predominantly female; 76% in 2023/24.

Male teachers are more likely to work in secondary schools than nurseries and primary schools: 14% of nursery and primary school teachers are male, 35% of secondary school teachers and 25% of teachers in special schools and state-funded alternative provision schools including PRUs.

Female teachers are less likely than their male counterparts to be in leadership positions (head teachers, deputy heads, assistant heads), however this difference has reduced over time. In 2023/24, 69% of leadership teachers were female, up from 66% in 2010/11. This compares to 77% of classroom teachers in 2023/24 and 76% in 2010/11. For a deeper analysis of teacher gender in leadership positions see School leadership in England 2010 to 2020: characteristics and trends. (opens in a new tab)

The ethnic diversity of the teacher workforce continues to increase, with 16.2% of teachers identifying as belonging to an ethnic minority group, up from 11.2% in 2010/11. Within these percentages, white minorities accounted for 5.3% of teachers,