McKinsey Problem Solving: Six steps to solve any problem and tell a persuasive story

The McKinsey problem solving process is a series of mindset shifts and structured approaches to thinking about and solving challenging problems. It is a useful approach for anyone working in the knowledge and information economy and needs to communicate ideas to other people.

Over the past several years of creating StrategyU, advising an undergraduates consulting group and running workshops for clients, I have found over and over again that the principles taught on this site and in this guide are a powerful way to improve the type of work and communication you do in a business setting.

When I first set out to teach these skills to the undergraduate consulting group at my alma mater, I was still working at BCG. I was spending my day building compelling presentations, yet was at a loss for how to teach these principles to the students I would talk with at night.

Through many rounds of iteration, I was able to land on a structured process and way of framing some of these principles such that people could immediately apply them to their work.

While the “official” McKinsey problem solving process is seven steps, I have outline my own spin on things – from experience at McKinsey and Boston Consulting Group. Here are six steps that will help you solve problems like a McKinsey Consultant:

Step #1: School is over, stop worrying about “what” to make and worry about the process, or the “how”

When I reflect back on my first role at McKinsey, I realize that my biggest challenge was unlearning everything I had learned over the previous 23 years. Throughout school you are asked to do specific things. For example, you are asked to write a 5 page paper on Benjamin Franklin — double spaced, 12 font and answering two or three specific questions.

In school, to be successful you follow these rules as close as you can. However, in consulting there are no rules on the “what.” Typically the problem you are asked to solve is ambiguous and complex — exactly why they hire you. In consulting, you are taught the rules around the “how” and have to then fill in the what.

The “how” can be taught and this entire site is founded on that belief. Here are some principles to get started:

Step #2: Thinking like a consultant requires a mindset shift

There are two pre-requisites to thinking like a consultant. Without these two traits you will struggle:

- A healthy obsession looking for a “better way” to do things

- Being open minded to shifting ideas and other approaches

In business school, I was sitting in one class when I noticed that all my classmates were doing the same thing — everyone was coming up with reasons why something should should not be done.

As I’ve spent more time working, I’ve realized this is a common phenomenon. The more you learn, the easier it becomes to come up with reasons to support the current state of affairs — likely driven by the status quo bias — an emotional state that favors not changing things. Even the best consultants will experience this emotion, but they are good at identifying it and pushing forward.

Key point : Creating an effective and persuasive consulting like presentation requires a comfort with uncertainty combined with a slightly delusional belief that you can figure anything out.

Step #3: Define the problem and make sure you are not solving a symptom

Before doing the work, time should be spent on defining the actual problem. Too often, people are solutions focused when they think about fixing something. Let’s say a company is struggling with profitability. Someone might define the problem as “we do not have enough growth.” This is jumping ahead to solutions — the goal may be to drive more growth, but this is not the actual issue. It is a symptom of a deeper problem.

Consider the following information:

- Costs have remained relatively constant and are actually below industry average so revenue must be the issue

- Revenue has been increasing, but at a slowing rate

- This company sells widgets and have had no slowdown on the number of units it has sold over the last five years

- However, the price per widget is actually below where it was five years ago

- There have been new entrants in the market in the last three years that have been backed by Venture Capital money and are aggressively pricing their products below costs

In a real-life project there will definitely be much more information and a team may take a full week coming up with a problem statement . Given the information above, we may come up with the following problem statement:

Problem Statement : The company is struggling to increase profitability due to decreasing prices driven by new entrants in the market. The company does not have a clear strategy to respond to the price pressure from competitors and lacks an overall product strategy to compete in this market.

Step 4: Dive in, make hypotheses and try to figure out how to “solve” the problem

Now the fun starts!

There are generally two approaches to thinking about information in a structured way and going back and forth between the two modes is what the consulting process is founded on.

First is top-down . This is what you should start with, especially for a newer “consultant.” This involves taking the problem statement and structuring an approach. This means developing multiple hypotheses — key questions you can either prove or disprove.

Given our problem statement, you may develop the following three hypotheses:

- Company X has room to improve its pricing strategy to increase profitability

- Company X can explore new market opportunities unlocked by new entrants

- Company X can explore new business models or operating models due to advances in technology

As you can see, these three statements identify different areas you can research and either prove or disprove. In a consulting team, you may have a “workstream leader” for each statement.

Once you establish the structure you you may shift to the second type of analysis: a bottom-up approach . This involves doing deep research around your problem statement, testing your hypotheses, running different analysis and continuing to ask more questions. As you do the analysis, you will begin to see different patterns that may unlock new questions, change your thinking or even confirm your existing hypotheses. You may need to tweak your hypotheses and structure as you learn new information.

A project vacillates many times between these two approaches. Here is a hypothetical timeline of a project:

Step 5: Make a slides like a consultant

The next step is taking the structure and research and turning it into a slide. When people see slides from McKinsey and BCG, they see something that is compelling and unique, but don’t really understand all the work that goes into those slides. Both companies have a healthy obsession (maybe not to some people!) with how things look, how things are structured and how they are presented.

They also don’t understand how much work is spent on telling a compelling “story.” The biggest mistake people make in the business world is mistaking showing a lot of information versus telling a compelling story. This is an easy mistake to make — especially if you are the one that did hours of analysis. It may seem important, but when it comes down to making a slide and a presentation, you end up deleting more information rather than adding. You really need to remember the following:

Data matters, but stories change hearts and minds

Here are four quick ways to improve your presentations:

Tip #1 — Format, format, format

Both McKinsey and BCG had style templates that were obsessively followed. Some key rules I like to follow:

- Make sure all text within your slide body is the same font size (harder than you would think)

- Do not go outside of the margins into the white space on the side

- All titles throughout the presentation should be 2 lines or less and stay the same font size

- Each slide should typically only make one strong point

Tip #2 — Titles are the takeaway

The title of the slide should be the key insight or takeaway and the slide area should prove the point. The below slide is an oversimplification of this:

Even in consulting, I found that people struggled with simplifying a message to one key theme per slide. If something is going to be presented live, the simpler the better. In reality, you are often giving someone presentations that they will read in depth and more information may make sense.

To go deeper, check out these 20 presentation and powerpoint tips .

Tip #3 — Have “MECE” Ideas for max persuasion

“MECE” means mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive — meaning all points listed cover the entire range of ideas while also being unique and differentiated from each other.

An extreme example would be this:

- Slide title: There are seven continents

- Slide content: The seven continents are North America, South America, Europe, Africa Asia, Antarctica, Australia

The list of continents provides seven distinct points that when taken together are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive . The MECE principle is not perfect — it is more of an ideal to push your logic in the right direction. Use it to continually improve and refine your story.

Applying this to a profitability problem at the highest level would look like this:

Goal: Increase profitability

2nd level: We can increase revenue or decrease costs

3rd level: We can increase revenue by selling more or increasing prices

Each level is MECE. It is almost impossible to argue against any of this (unless you are willing to commit accounting fraud!).

Tip #4 — Leveraging the Pyramid Principle

The pyramid principle is an approach popularized by Barbara Minto and essential to the structured problem solving approach I learned at McKinsey. Learning this approach has changed the way I look at any presentation since.

Here is a rough outline of how you can think about the pyramid principle as a way to structure a presentation:

As you build a presentation, you may have three sections for each hypothesis. As you think about the overall story, the three hypothesis (and the supporting evidence) will build on each other as a “story” to answer the defined problem. There are two ways to think about doing this — using inductive or deductive reasoning:

If we go back to our profitability example from above, you would say that increasing profitability was the core issue we developed. Lets assume that through research we found that our three hypotheses were true. Given this, you may start to build a high level presentation around the following three points:

These three ideas not only are distinct but they also build on each other. Combined, they tell a story of what the company should do and how they should react. Each of these three “points” may be a separate section in the presentation followed by several pages of detailed analysis. There may also be a shorter executive summary version of 5–10 pages that gives the high level story without as much data and analysis.

Step 6: The only way to improve is to get feedback and continue to practice

Ultimately, this process is not something you will master overnight. I’ve been consulting, either working for a firm or on my own for more than 10 years and am still looking for ways to make better presentations, become more persuasive and get feedback on individual slides.

The process never ends.

The best way to improve fast is to be working on a great team . Look for people around you that do this well and ask them for feedback. The more feedback, the more iterations and more presentations you make, the better you will become. Good luck!

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll get a kick out of all the free lessons I’ve shared that go a bit deeper. Check them out here .

Do you have a toolkit for business problem solving? I created Think Like a Strategy Consultant as an online course to make the tools of strategy consultants accessible to driven professionals, executives, and consultants. This course teaches you how to synthesize information into compelling insights, structure your information in ways that help you solve problems, and develop presentations that resonate at the C-Level. Click here to learn more or if you are interested in getting started now.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Get the Free Mini-Course

Learn to solve complex problems, write compellingly, and upgrade your thinking with our free mini-course.

Work With Us

Join 1,000+ professionals and students learning consulting skills and accelerating their careers

30% Off Everything

- Strategy Templates

Consulting Templates

- Market Analysis Templates

- Business Case

- Consulting Proposal

- Due Diligence Report

All Templates

The mckinsey problem solving process - a step-by-step guide.

Table of contents

Hypothesis-led problem solving, step 1: define the problem, step 2: structure the problem, step 3. prioritizing issues, step 4. develop issue analysis/work plan, step 5. conduct analyses, step 6: synthesize findings, step 7. developing recommendations.

Problem-solving—finding the best solution to a business opportunity or challenge—is at the heart of how management consultants create impact for their clients.

At McKinsey, there’s a proven method of problem solving that every associate learns from day one—a structured, step-by-step approach that can be applied to almost any business problem.

This post will guide you through that approach, offering practical tips, tricks, and free templates so you can start applying these techniques right away.

There are a number problem solving approaches being used at McKinsey, each suited for different types of problems.

This article focuses on the hypothesis-led approach —McKinsey’s go-to method for addressing most business challenges—which emphasizes forming and testing hypotheses to arrive at impactful solutions efficiently.

The hypothesis-led problem-solving approach is particularly effective when problems are complex and data may be incomplete, such as market entry strategies, business strategy development, mergers and acquisitions, and operational improvements.

Here are the seven steps involved in this process:

- Define problem - What key question do we need to answer?

- Structure problem – What could be the key elements of the problem?

- Prioritize issues – Which issues are most important to the problem?

- Develop issue analysis/work plan – Where and how should we spend our time?

- Conduct analyses – What are we trying to prove/disprove

- Synthesize findings – What implications do our findings have?

- Develop recommendations – What should we do?

Please note that although these steps are listed in order, problem-solving is not a straight line. Think of it as an iterative process where you quickly develop early hypotheses and solutions and continually refine them.

Let’s go through the seven steps in detail one by one:

McKinsey’s problem solving process starts with a clear and thorough definition of the problem and the end goal .

It’s tempting to rush this step—perhaps you think you already know the solution, or you believe the problem was already clearly outlined in the project assignment, or you feel pressured by stakeholders to proceed quickly. And while all these reasons might be valid, many unsuccessful projects stem from not having a clear definition of the problem and a shared understanding of what success looks like.

Great problem solvers take the time to establish a precise and comprehensive definition of the real issue at hand. And they make sure that this definition is understood and agreed upon by all relevant stakeholders as well as within the project team.

Using the Problem Statement Worksheet

To define the problem effectively, we recommend using the Problem Statement Worksheet (can be found here ). It looks simple, but it is very effective.

By thoroughly working through the Problem Statement Worksheet, you set a strong foundation for the rest of the problem-solving process, ensuring that everyone is aligned and focused on delivering the right solution. If you are unclear about an element of the Problem Statement Worksheet, it will almost always result in ‘scope creep’ or unaligned expectations.

A few tips on how to maximize the value of the Worksheet:

- Main question to be resolved : Make the main question SMART —Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, Relevant, and Time-bound. For example, “How can Airline Inc. reduce operating costs by $400 million through more efficient and effective operations before 2027?” is a SMART question.

- Context : Discuss the environment in which the client operates. Consider internal and external factors like industry trends, competitive position, capability gaps, and financial flexibility (a market analysis template might be helpful here).

- Success Criteria : Clarify how key stakeholders define success and failure. Beyond quantitative goals, identify other important measures like timing, visibility of improvements, required capability building, and necessary mindset shifts.

- Scope and Constraints : Define what’s included and what’s not. Start by outlining the scope—for instance, the markets or segments of interest. Then specify any constraints within that scope, such as focusing on organic growth options only.

- Stakeholders : Identify who the key decision-makers are. Understanding who decides, who can help, and who might block progress is crucial from the outset.

- Key Sources of Insight : Determine the expertise and knowledge you’ll need. This could include internal resources like company experts and data sources, as well as external insights from experts, suppliers, and customers.

After defining the problem, the next step is to structure the problem effectively. This involves breaking down the main question into smaller, manageable parts that can be analyzed and addressed. Two powerful techniques for this are hypothesis trees and issue trees .

Hypothesis Trees

A hypothesis tree is a structured tool that breaks down your main problem into a hierarchy of testable hypotheses. Starting from the main question, you systematically decompose it into smaller, more manageable parts that can be individually analyzed and validated.

This approach helps you focus your efforts on the most critical areas, streamline your analysis, and move efficiently toward a solution. Example:

If the primary question is, “How can Airline Inc. reduce operating costs by $400 million through more efficient and effective operations before 2027?” you might develop the following hypotheses:

- Fleet Optimization : Airline Inc. can save $150 million by optimizing its fleet operations.

- Operational Efficiency : Airline Inc. can achieve $120 million in savings through process improvements and better resource allocation.

- Supplier and Procurement Optimization : By renegotiating supplier contracts and optimizing procurement processes, Airline Inc. can reduce costs by $80 million.

- Technology and Automation : Investing in technology and automation can achieve $50 million in savings.

Each of these hypotheses can then be broken down further and tested through analysis.

What makes a good hypothesis?

A strong hypothesis should:

- Be testable : You can prove or disprove it with data and analysis.

- Invite debate : It should be open to challenge, not a statement of fact.

- Matter to the outcome : If the opposite of your hypothesis wouldn’t affect the solution, it’s not significant.

- Lead to Action : It should point toward specific actions the company can take.

- Avoid Obviousness : It shouldn’t be something the client already knows without analysis.

Issue Trees

When you don’t have enough information to form specific hypotheses upfront, an issue tree is an effective tool to break down the main problem into key questions that need answering. Issue trees help you systematically explore all aspects of a complex problem by decomposing it into smaller, manageable issues or questions. This approach ensures that you cover all possible angles and don’t overlook any critical factors.

Example: Continuing with the operational costs of Airline Inc., your issue tree might look like this:

Tips for Effective Issue Trees:

- Start with the main question and break it down into smaller components.

- Use open-ended questions starting with “what,” “how,” or “why” to encourage deeper exploration.

- Ensure your issues are Mutually Exclusive (they don’t overlap) and Collectively Exhaustive (they cover all possible areas) - aka. MECE

After breaking down the problem into hypotheses or key issues, the next step is prioritizing which ones to tackle first. Effective prioritization ensures that your efforts are focused on the areas that will deliver the most significant impact.

A common tool for prioritization is the two-by-two matrix , which helps visualize and compare different issues based on specific criteria.

Choose two criteria that are most relevant to your project’s success. The most frequently used axes are:

- Impact : The potential of the issue to contribute to solving the main problem.

- Ease of Implementation : How straightforward it is to address the issue, considering factors like resources, time, and complexity.

Other commonly used prioritization criteria include urgency, fit with values and mission, strategic alignment, and fit with capabilities. Applying some of these prioritization criteria will typically knock out portions of the issue tree altogether, enabling you to focus your efforts where they matter most.

With your prioritized list of key issues or hypotheses, the next step is to design an effective work plan outlining how you’ll conduct the necessary analyses to address each issue plan the analyses needed to test these hypotheses and develop solutions. Turning your prioritized problems into a work plan involves two main steps:

First , define the tasks that need to be completed. Whether you’re starting from issues or hypotheses, clearly outline the desired outcomes and the analyses required to achieve them. Also, estimate the data sources, timing and who will be responsible for each.

Next , organize these tasks in a timeline that aligns with available resources and key project milestones (like important meetings or progress reviews). Make sure the sequence fits the overall pace of the project, such as weekly or bi-weekly meetings.

After putting together your work plan, the next step is gathering data and conducting analyses to solve the problem at hand. This step typically takes up most of the time spent on a consulting project.

While this guide doesn’t aim to teach you how to collect data or perform analyses, it’s important to emphasize that at McKinsey, quantitative data is paramount. Any solution not backed by solid numbers carries a heavy burden of proof. If data isn’t readily available, you must generate it yourself—whether through interviews, surveys, or constructing models.

Tips for this step

- Focus on solutions, not just analysis : Always aim for the end result. Don’t get caught up in just “running the numbers.”

- Simpler is often better : Your solutions must be thorough, but that doesn’t mean every detail needs weeks of research. Often, quickly finding a “good enough” answer is more valuable than taking extra time to perfect it. Quick estimates and rough calculations can guide more detailed analyses when needed. Generally, use the 80/20 rule : focus on the 20% of analysis that provides 80% of the solution.

After diving deep into data and analysis, it’s essential to step back and identify what’s truly important. This is often the most challenging part of problem-solving. Effective problem solvers look for the core message that will support a clear recommendation.

At McKinsey, the Pyramid Principle is used to synthesize findings. This principle states that every synthesis should communicate one main idea—the “governing thought.” Supporting ideas are organized logically, moving from detailed facts up to the main conclusion, while excluding irrelevant information.

Even though synthesizing formally comes near the end of the problem solving process, it’s something you should do continuously throughout the project. After making any analytical progress, try to create an initial “Day 1” or “Week 1” draft of your solution and revisit it regularly—testing and adjusting both your answers and your approach at each phase. Regular synthesis helps keep your team focused on the key question and ensures you’re always ready to communicate your findings.

This step involves translating your overall solution into specific actions that will deliver impact. This is where we answer the main question: “What should we do, and how should we do it?” While thorough analysis is important, it has little value if it doesn’t lead to actionable recommendations along with a plan and leadership commitment to implement the plan.

Steps to develop effective recommendations:

- Create a practical action plan : Outline the necessary initiatives with clear sequences, timelines, and activities. Consider the need for lasting impact, quick wins, available resources, and any competing priorities.

- Assign clear ownership : Identify who will be responsible for each initiative.

- Identify success factors and challenges : Highlight what will be critical for success and any potential obstacles, such as individuals who can drive change or those who might resist it.

When building your recommendations, consider these questions:

- Does everyone who needs to change understand what they need to do and why?

- Are key leaders committed to changing their behavior?

- Have you established systems (like evaluations or incentives) to support the desired change?

- Do we have the skills and confidence to adopt the new ways of working?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, ensure your recommendations address these issues. By doing so, you’ll increase the odds of achieving results.

Tips for Synthesizing findings A powerful way to synthesize the overall story is to structure your synthesis using the 'Situation, Complication, and Resolution' framework (SCR framework).

- Situation : What’s the current context or reason for action?

- Complication : What’s the challenge that needs addressing?

- Resolution : What’s your proposed solution?

Example: Situation : “The airline industry is under pressure to reduce costs due to rising fuel prices, increased competition, and post-pandemic recovery challenges. Complication : “Airline Inc.’s operating costs are significantly higher than industry benchmarks, threatening profitability and limiting its ability to invest in growth opportunities.” Resolution : “Airline Inc. should implement a comprehensive cost-reduction strategy targeting $400 million in savings by 2027, focusing on fleet optimization, operational efficiency, supplier renegotiations, and technology-driven automation.”

Read more about the SCR-framework here.

Communication and collaboration

Effective problem-solving is closely linked with communication. Throughout the problem solving process, maintain open lines of communication with team members and stakeholders. Share your draft solutions to ensure they’re practical and impactful—not just good on paper. Co-creating the solution with relevant stakeholders sharpens the outcome, uncovers potential issues early, and fosters ownership of the final recommendations.

Further Reading

Hope you enjoyed this post. If you’re interested in diving deeper into related concepts, check out these insightful posts:

- The Pyramid Principle - Explore how the Pyramid Principle can help you structure your thoughts and arguments in a logical, top-down approach.

- How to use McKinsey's SCR framework - Learn more about the Situation-Complication-Resolution framework and how it can be applied to problem-solving and strategic thinking.

- What is the MECE Framework? - Discover how the MECE principle ensures thorough and organized problem analysis.

- How McKinsey Consultants Make PowerPoint Presentations - Understand the structure of a McKinsey presentation, its key elements, and formatting tips and tricks.

Download our most popular templates

High-end PowerPoint templates and toolkits created by ex-McKinsey, BCG, and Bain consultants

Consulting toolkit and template

A comprehensive library of slide layouts, templates, and typical consulting tools and frameworks.

- Business Strategy

This template, created by ex-McKinsey and BCG consultants, includes everything you need to create a complete strategy.

- Market Analysis

Create a full market analysis report to effectively turn your market research into strategic insights

Related articles

Management consulting fees: How McKinsey prices projects

In this article, we’ll explain how consulting projects are priced and the different types of pricing, dive into why firms like McKinsey typically favor fixed fees, explore the range of consulting fees across the industry, and show some real examples of BCG and McKinsey projects and how they were priced.

Dec 7, 2024

How to write a Next Steps slide (with Examples and Free Template)

In this blog post, we’ll dive into the Next Steps slide, why it’s important, and how to write one. We’ll also provide you with examples of Next Steps slides from McKinsey, BCG, and Bain, as well as a free template for you to create your own Next Steps slide.

Nov 1, 2024

Picking apart a McKinsey consulting proposal

In this blog post, we’ll break down a McKinsey consulting proposal, look at what works and why, and discuss how to write a winning consulting proposal.

Oct 12, 2024

- Consulting Toolkit

- Market Entry Analysis

- Consulting Maps Bundle

- Mergers & Acquisitions

- Digital Transformation

- Product Strategy

- Go-To-Market Strategy

- Operational Excellence I

- Operational Excellence II

- Operational Excellence III

- Full Access Bundle

- Consulting PowerPoint Templates

- How it works

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

© 2024 Slideworks. All rights reserved

Denmark : Farvergade 10 4. 1463 Copenhagen K

US : 101 Avenue of the Americas, 9th Floor 10013, New York

McKinsey Staff Paper - No. 66 - July 2007 - The McKinsey Approach to Problem Solving

Related documents

27 Pages • 11,388 Words • PDF • 1.1 MB

143 Pages • PDF • 6.2 MB

240 Pages • 61,065 Words • PDF • 1.5 MB

207 Pages • 42,414 Words • PDF • 826.8 KB

26 Pages • 7,364 Words • PDF • 604.4 KB

23 Pages • 5,939 Words • PDF • 233.1 KB

24 Pages • 7,246 Words • PDF • 589.9 KB

231 Pages • 27,979 Words • PDF • 26.4 MB

28 Pages • 7,015 Words • PDF • 359.1 KB

120 Pages • 28,910 Words • PDF • 1.7 MB

293 Pages • 108,798 Words • PDF • 2 MB

979 Pages • 475,273 Words • PDF • 88.8 MB

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

Read more > Listen to the podcast (duration: 24:30) > Structured problem solving can be used to address almost any complex challenge in business or public policy.

See www.mckinsey.com/privacy-policy for privacy information

Hosts & Guests

Lucia rahilly, roberta fusaro, simon london, charles r. conn, hugo sarrazin, information.

- Show The McKinsey Podcast

- Frequency Updated Biweekly

- Published July 29, 2021 at 2:00 PM UTC

- Length 25 min

- Rating Clean

To listen to explicit episodes, sign in.

Stay up to date with this show

Sign in or sign up to follow shows, save episodes, and get the latest updates.

Africa, Middle East, and India

- Brunei Darussalam

- Burkina Faso

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Congo, The Democratic Republic Of The

- Guinea-Bissau

- Niger (English)

- Congo, Republic of

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- Tanzania, United Republic Of

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

Asia Pacific

- Indonesia (English)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Malaysia (English)

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- New Zealand

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Solomon Islands

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- France (Français)

- Deutschland

- Luxembourg (English)

- Moldova, Republic Of

- North Macedonia

- Portugal (Português)

- Türkiye (English)

- United Kingdom

Latin America and the Caribbean

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Argentina (Español)

- Bolivia (Español)

- Virgin Islands, British

- Cayman Islands

- Chile (Español)

- Colombia (Español)

- Costa Rica (Español)

- República Dominicana

- Ecuador (Español)

- El Salvador (Español)

- Guatemala (Español)

- Honduras (Español)

- Nicaragua (Español)

- Paraguay (Español)

- St. Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- St. Vincent and The Grenadines

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turks and Caicos

- Uruguay (English)

- Venezuela (Español)

The United States and Canada

- Canada (English)

- Canada (Français)

- United States

- Estados Unidos (Español México)

- الولايات المتحدة

- États-Unis (Français France)

- Estados Unidos (Português Brasil)

- 美國 (繁體中文台灣)

Product Mindset's Newsletter

Share this post.

25/36 : 🛠️ McKinsey's Problem-solving Process

A problem well defined is a problem half-solved — charles kettering.

Problem Solving for Product Managers

Product Managers excel in problem-solving by employing a strategic mix of analytical thinking, creative ideation, and data-driven insights. They keenly identify and comprehend customer needs, analyze market trends, and craft innovative solutions that enhance products' value and propel business growth. By addressing challenges, optimizing development processes, and aligning products with company objectives, they ensure customer demands are met efficiently and deliver successful outcomes.

Concept of problem-solving

Today's businesses want employees who can adapt to new situations rapidly and effectively.

The ideal employee is a master of basic skills such as reading, writing, and numeracy.

The ideal employee is also a master of learning, communication, critical thinking, creative thinking, and problem-solving.

The ideal employee can respond to a problem quickly, correctly, and with little or no supervision.

If you can solve problems, you can write your own ticket for whatever job you want.

Defining Problem-Solving

Problems can be classified into puzzle problems, well-structured problems, and ill-structured problems.

Simple Problems Many games contain puzzle problems and are not "serious" in nature, nor is there any real-life consequence for failing to solve them.

Well-structured Problems Some problems which are simple and well-defined are called well-structured problems and include a set number of possible solutions - solutions are either 100% right or 100% wrong. An example of a well-structured problem is a typical mathematical (2 + 2 = 4) question. This question has a definitive correct answer.

Ill-structured Problems In contrast to well-structured problems are ill-structured problems. In these cases, problems may have many possible answers because they are complex and poorly defined. The "best" solutions to ill-defined problems depend on the priorities underlying the situation. What is "best" today may not be "best" tomorrow. Ill-structured problems, because they are more difficult to "solve," require the development of higher-order thinking skills and the ability to construct a convincing argument for a particular solution as opposed to all other possible solutions.

To summarize ill-structured problems:

They are complex and poorly defined.

They have many possible answers.

They do not have one best answer.

Here is an example of an ill-structured problem:

The population of your community is growing. Your water supply will not support many new people.

What do you do?

This is a complex problem. It affects the people, the environment, and the quality of life itself. To arrive at a good solution, you need to use math, science, political science, psychology, and probably more!

This problem actually occurs frequently in areas with a growing population. In one community facing this problem, more than 20 possible solutions were presented to the public. A solution was then chosen upon which the majority of the public agreed. It wasn't the "right" solution because all of the 20 possible solutions had strengths and weaknesses.

The lesson here is that ill-structured problems usually have several workable solutions. Each solution has advantages and disadvantages that depend on who is affected by the solution. The solution chosen is often the one that has the best argument for it.

3 Prerequisites for a good solution

He realized there are three essential prerequisites for good solutions:

The product must be defined to allow for the development of useful solutions. The potential solution must fit the defined problem space and product scope. The product team must have understood the problem.

Understanding the problem Whether the problem comes from your users or another set of stakeholders, you need to properly understand the problem. The only way to do that is through a combination of research, and empathy. This means gathering both qualitative and quantitative data. Find out how the user/stakeholder feels about the problem, as well as how they behave in response to it.

Communicate “The Why” As a product manager, your most important why is the customer problem that your product is trying to solve. Include your team and other stakeholders in understanding the customer problem and selecting the right goal metric to grow. This way, everyone can contribute, feel ownership, and stay motivated to solve the problem even if the product changes.

First , it helps everyone internalize “the why” so they can make decisions with the same goal in mind.

Second , if people are not aligned on “the why”, they’re more likely to bring up objections if you talk about it constantly.

Keep It Simple When communicating with others, the most critical question that you need to answer is, “Do people understand?” If people don’t understand the why, they won’t be able to execute.

Keep your communication simple, short, and specific. Check to see if people understand your message by asking them to explain it back to you

Make a risk vs reward assessment Once you know what the problem is, you need to lay the groundwork for your plan on how to proceed with solving it. Analyze the potential risks and rewards of the project. So if a stakeholder is asking that a new feature be implemented, work out how much of your team’s work hours, budget, and resources will be needed to complete the project and solve the problem.

Balance this out by seeing how the best-case scenario (eg, you completely solve the problem) will benefit your product in terms of OKRs, and the bottom line.

Define Success Defining the success of a project really boils down to the final part of your risk vs reward assessment. What does the best-case scenario look like?

If the answer isn’t obvious, think about your company’s North Star metrics, or your team’s KPIs. If the project is worthwhile, its goals should align with either, if not both, or these.

I learned to approach every problem from multiple angles. It was the combination of both qualitative and quantitative insights that led us to our proposed solution. Also, a variety of perspectives are critical.

Learning to Ask the Right Questions: Define the Problem Statement

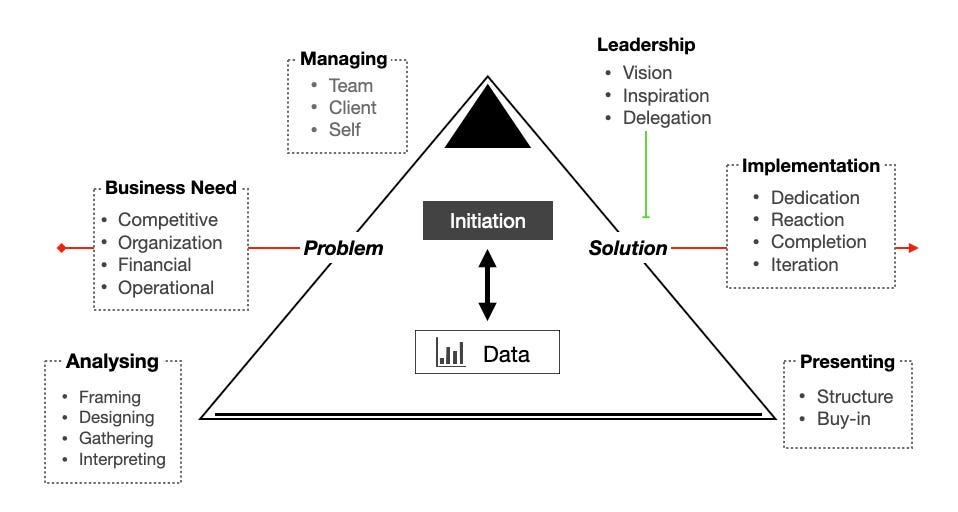

McKinsey’s Problem-solving process

McKinsey’s benchmark is the problem-solving process as practiced by McKinsey. At the most abstract level, McKinsey develops solutions to clients’ strategic problems and, possibly, aids in the implementation of those solutions

Business Need You can’t have problem-solving without a problem or, more broadly, a need on the part of the client. In business, those needs come in several forms: competitive, organizational, financial, and operational.

Analyzing Once your organization has identified the problem, it can begin to seek a solution, whether on its own or with the help of McKinsey (or any other outside agent). McKinsey’s fact-based, hypothesis-driven problem-solving process begins with framing the problem: defining the boundaries of the problem and breaking it down into its component elements to allow the problem-solving team to come up with an initial hypothesis as to the solution. The next step is designing the analysis, determining the analyses that must be done to prove the hypothesis, followed by gathering the data needed for the analyses. Finally comes interpreting the results of those analyses to see whether they prove or disprove the hypothesis and to develop a course of action for the client.

Presenting You may have found a solution, but it has no value until it has been communicated to and accepted by the client. For that to happen, you must structure your presentation so that it communicates your ideas clearly and concisely and generates buy-in for your solution for each individual audience to which you present.

Managing The success of the problem-solving process requires good management at several levels. The problem-solving team must be properly assembled, motivated, and developed. The client must be kept informed, involved, and inspired by both the problem-solving process and the solution. The individual team members (that’s you) must strike a balance between life and career that allows them to meet the expectations of the client and the team while not “burning out.”

Implementation Your organization may have accepted your solution, but it must still implement it. This requires the dedication of sufficient resources within the organization, the timely reaction of the organization to any stumbling blocks that may arise during implementation, and the focus of the organization on completion of the tasks necessary for full implementation. In addition, the organization must institute a process of iteration that leads to continual improvement. That process requires reassessing implementation and rededicating the organization to make additional changes identified during reassessment.

Leadership At the nexus of solution and implementation comes leadership. Those at the helm of your organization must conceive a strategic vision for the organization. They must also provide inspiration for those in the organization who will do the hands-on work of implementation. Finally, they must make the right judgments regarding the delegation of authority in overseeing implementation throughout the organization.

There is one other piece of the model: the tension between intuition and data. Problem-solving doesn’t take place in a vacuum. Even McKinsey has only so many resources to throw at a problem and a limited time in which to solve it. While we are advocates for McKinsey-style fact-based problem solving, we recognize that it’s practically impossible to have all the relevant facts before reaching a decision. Therefore, most executives make business decisions based partly on facts and partly on intuition—gut instinct tempered by experience. We will discuss the pros and cons of each element later in the book. For now, we will simply say that we think a sound decision requires a balance of both.

8 Steps to Problem-Solving from McKinsey

Solve at the first meeting with a hypothesis, intuition is as important as facts, do your research but don’t reinvent the wheel, tell the story behind the data, start with the conclusion, hit singles, respect your time.

The McKinsey problem-solving process begins with the use of structured frameworks to generate fact-based hypotheses followed by data gathering and analysis to prove or disprove the hypotheses.

Gut feeling at this stage is extremely important because we don’t have many facts yet. However, structure strengthens your thinking and ensures that your ideas will stand up. Typically, the problem-solving process would involve defining the boundaries of the problem and then breaking it down into its component elements.

The concept of MECE (pronounced “mee-see” and an acronym for Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive), is a basic tenet of the McKinsey thought process. Being MECE in the context of problem-solving means separating your problem into distinct, non-overlapping issues while making sure that no issues relevant to your problem have been overlooked. This allows to simplify the problem and plan the work because in most cases, a complex problem can be reduced to a group of smaller, simpler problems that can be solved individually.

The most common tool McKinsey people use to break problems apart is the logic tree .

Having reduced the problem to its essential components, you are ready to embark on the next step which is framing it: forming a hypothesis as to its likely solution. By already knowing where your solution is, you eliminate a lot of paths that lead to dead ends.

Using an initial hypothesis to guide your research and analysis will increase both the efficiency and effectiveness of your decision-making because it provides you and your team with a problem-solving roadmap that will lead you to ask the right questions and perform the correct analysis to get to your answer. A good hypothesis will also save you time by pointing out potential blind alleys much more quickly and allowing you to get back to the main issues if you do go down the wrong path.

Since you should form your hypothesis at the start of the problem-solving process, you have to rely less on facts (you won’t have done most of your fact gathering yet) and more on instinct or intuition. Take what you know about the problem at hand, combine it with your gut feelings on the issue, and think about what the most likely answers are.

Executives make major strategic decisions based as much on gut instinct as on fact-based analysis.

Intuition and data complement each other. You need at least some of each to have a solid basis for your decisions. The key to striking the balance is quality over quantity.

When you form an initial hypothesis, you are “solving the problem at the first meeting.” Unfortunately, although you may think you have the answer, you have to prove it through fact-based analysis.

Your next step is to figure out which analyses you have to perform and which questions you have to ask in order to prove or disprove your hypothesis.

When your time and resources are limited, you don’t have the luxury of being able to examine every single factor in detail. Instead, when planning your analyses, figure out which factors most affect the problem and focus on those. Drill down to the core of the problem instead of picking apart each and every piece. In most situations, achieving a scientific level of exactitude for your management decisions is counterproductive.

That’s why also as one of your first steps in designing your analysis, you should figure out what not to do.

As your next step, you should decide which analyses are quick wins — easy to complete and likely to make a major contribution to proving or refuting the initial hypothesis (80/20 rule).

When doing your research, you don’t want to get as much information as possible, you want to get the most important information as quickly as possible.

With a plan of action for what to research, make sure you don’t reinvent the wheel as you start gathering your data. Whatever problem you’re facing, chances are that someone somewhere has worked on something similar. So your next step here is to look through all possible internal documents and then look externally.

Once you have your analysis finished, you need to interpret it because numbers or data don’t say anything. You have to figure out the story behind it and the message that you want to communicate.

At this stage, first comes the process of understanding the data: piecing together (in your own mind or within your team) the story the data is telling you and the steps you should take based on that story. The second comes assembling your findings into an externally directed end product: a key message that includes a course of action for your organization, ream, or client.

Your interpretation of the data leads to a story, that is, what you think the data means. You select those portions of the story that you believe your audience needs to know in order to understand your conclusion, along with the supporting evidence, and you put them together into your end product as in your presentation.

To succeed here you need to see through your client’s, executive’s or audience’s lenses and speak their language.

The key to successful presentations and getting buy-in (in order for your audience to accept your recommendations) is prewiring.

The reason behind this is because to get the buy-in you need to bridge the information and trust gaps between you and your audience. The information gap exists because you know more about your findings than your audience does. Depending on the relationship between you and your audience, the trust gap (if it exists) could take any of several forms. Your audience may think that you are too inexperienced to comment on their business, or they may mistrust you because you are an outsider, are overeducated, or not educated enough.

In its essence, prewiring means taking your audience through your findings before you give your presentation. This allows for people to trust you, ask questions you may not have thought about to avoid surprises, and then during the presentation say yes and support you among others who may be more skeptical.

Prewire everything. A good business presentation should contain no shocking revelations for the audience. Walk the relevant decision-makers in your organization through your findings before you gather them together for a dog and pony show. At a minimum, you should send out your recommendations via email to request comments from key decision-makers before the presentation if you can’t meet with those people face-to-face.

The earlier you can start the prewiring process, the better. By identifying and getting input from the relevant players early on, you allow them to put their own mark on your solution, which will make them more comfortable with it and give them a stake in the outcome.

When you begin your presentation in front of your desired audience, make sure you start with the conclusion.

Having your conclusions or recommendations upfront is sometimes known as inductive reasoning. Simply put, inductive reasoning takes the form, “We believe X because of reasons A, B, and C.” This contrasts with deductive reasoning, which can run along the lines of, “A is true, B is true, and C is true; therefore, we believe X.” Even in this simplest and most abstract example, it is obvious that inductive reasoning gets to the point a lot more quickly, takes less time to read, and packs a lot more punch.

As an additional advantage, starting with your conclusions allows you to control how far you go into detail in your presentation.

You need to explain this clearly within just 30 seconds. Almost like an elevator pitch. If you can pass this “elevator test,” then you understand what you’re doing well enough to sell your solution.

A successful presentation bridges the gap between you — the presenter — and your audience. It lets them know what you know.

It also keeps it simple for them which is why it’s important to stick to a key rule if you are using a deck: one message per slide or chart. No more. The more complex a chart/slide becomes, the less effective it is at conveying information. The meaning should be immediately obvious to the reader, so use whatever tools you need to bring it out.

If you broke out your initial hypothesis into a MECE set of issues and sub-issues (and suitably modified them according to the results of your analysis), then you have a ready-made outline for your presentation that will support your conclusion.

Remember that you have two ears and only one mouth. It’s not just what you say, it’s how you say it. Overcommunication is better than under-communication which is why prewiring as mentioned above is so important.

Finally, if you are proposing a certain solution in which you will be involved in the execution, make sure you don’t overpromise because you’re bound to under-deliver. Instead, balance the demands for the solution with your capabilities and those of your team. If more work is necessary, you can always start a second project once the first is done.

When you begin executing on the solution, aim to hit singles.

This is a metaphor from baseball. You can’t do everything, so don’t try. Just do what you’re supposed to do, and get it right. It’s impossible to do everything yourself all the time. If you do manage that feat once, you raise unrealistic expectations from those around you. Then, when you fail to meet those expectations, you’ll have difficulty regaining your credibility.

Getting on base consistently is much better than trying to hit a home run and striking out nine times out of ten.

Do few things well rather than a ton with mediocre execution or results. Stick to targeted focus rather than perfection and drilling into every little piece.

Quality over quantity. And when there’s a lot of work to be done, delegate around your limitations. Know them for what they are and respect them.

Don’t forget that work is like a gas: it expands to fill the time available.

As in the previous point, share the load by delegating and also perform sanity checks on the way to allow you to take a step back and look at the big picture.

You will also have to get others to respect your time. The better you are at your job or the higher up you go in your organization, the more everyone wants a piece of you. There’s an old saying, “Stress is the feeling you get when your gut says, ‘No,’ and your mouth says, ‘Yes, I’d be glad to.’” You have to train your mouth to say, “No.”

Once you make a commitment — “I won’t work on weekends” or “I’ll cook dinner three nights a week” — stick to it, barring life-and-death emergencies. If you seem to be having life-and-death emergencies every week (and you’re not dealing with matters of real life and death, as in a trauma ward), take a hard look at your priorities.

Share Product Mindset's Newsletter

Additional Reads :

1/36 - Product Discovery Process

2/36 - Pre-discovery Phase

3/36 - PD Preparation & Frameworks

4/36 - Double Diamond Discovery

5/36 - User-Centered Design

6/36 - Managing Product Ideas for Product Discovery

7/36 - Crafting a Problem Statement

8/36 - Product Logic Model : Input, Output, Outcome

9/36 - Understanding Problem Space

10/36 - User Research 101: Navigating the Discovery Process

11/36 - User Interviews Deep Drive

12/36 - User interview analysis – turning raw data into insights effectively

13/36 : Lean Prioritization Framework

14/36 : Understanding Solution Space

15/36 : Lean Experiment & Case Study

16/36 : 📈 Discover the Power of Product Metrics

17/36 : 🚀 Minimum Viable Product Playbook

18/36 :Product Discovery - Risks & Mitigations

19/36 : 🧠 Product Discovery - Inception

20/36 : 🧠 Outcome based Product roadmaps?

21/36 : DEEP Product Backlog

22/36 : BDD, Theme, Epic, Feature & Story

23/36 : 📚 A Guide to Effective User Stories and Story Mapping and Pointing

24/36 : 🔁 Continuous discovery & Product market matrix

Product Management Reading List For 2023

Discussion about this post

Ready for more?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Structured problem solving strategies can be used to address almost any complex challenge in business or public policy. ... Looked at this way, it's no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven ...

Become a better problem solver with insights and advice from leaders around the world on topics including developing a problem-solving mindset, solving problems in uncertain times, problem solving with AI, and much more. ... McKinsey Quarterly. Our flagship business publication has been defining and informing the senior-management agenda since ...

The McKinsey problem solving process is a series of mindset shifts and structured approaches to thinking about and solving challenging problems. It is a useful approach for anyone working in the knowledge and information economy and needs to communicate ideas to other people.

At McKinsey, there's a proven method of problem solving that every associate learns from day one—a structured, step-by-step approach that can be applied to almost any business problem. This post will guide you through that approach, offering practical tips, tricks, and free templates so you can start applying these techniques right away.

August 14, 2021 Knowing how to solve any problem thrown your way is a uniquely valuable skill. The good news is that it's a muscle you can develop and strengthen over time. Revisit several articles on tactics that can help you up your game, diving deeper on: mindsets to help unlock your problem-solving potential

In support of that goal, this staff paper sets out the "McKinsey method" of problem solving, a structured, inductive approach that consists of four fundamental disciplines: problem definition, the problem-solving process itself, a number of "distinctiveness practices" our strongest problem solvers apply to deliver superior results to ...

Structured problem solving can help address complex business challenges. Podcast Episode · The McKinsey Podcast · 07/29/2021 · 25m. Home; Browse; Top Charts; Search; 07/29/2021; 25 MIN; How to master the seven-step problem-solving process. The McKinsey Podcast. Play . Read more >

The McKinsey problem-solving process begins with the use of structured frameworks to generate fact-based hypotheses followed by data gathering and analysis to prove or disprove the hypotheses. ... Well-structured Problems Some problems which are simple and well-defined are called well-structured problems and include a set number of possible ...

The McKinsey 7-step problem-solving model is highly regarded for its systematic and iterative approach. It emphasizes clear problem definition, structured analysis, and thorough planning, which helps in addressing complex issues comprehensively. The model's iterative nature allows for continuous learning and adaptation, making it effective in ...

As a result, problem-solving skills are in great demand. McKinsey research shows that organizations that have top-quartile problem-solving capabilities earn 3.5 times higher total shareholder returns than those in the bottom quartile. This week, let's explore some structured approaches that can improve your problem-solving aptitude.